Exploiting the Feature Factory

Introduction

Hey hackers!

Bug Bounty is one of those fields where you need to reflect a lot. We read tons of articles, listen to the CTBB Podcast, gain experience...

But if we don't keep reflecting and evolving our methodology, what's the point of learning if we keep using our deprecated approach?

Personally, every month or so I dedicate some time to reflect on my strategies, methodologies, and performance. I evaluate what things I believe have worked well and what things I feel are leading me to stagnate or get frustrated.

I implement changes in my methodology and write down the key words I want to make sure I follow on a sticky note on my desk.

That way, every time I look at the sticky note, it forces me to think about whether I'm living up to what I wrote!

Lately I've been finding my first high and critical bugs, and although they had significant impact, they weren't exactly rocket science, but about scope selection and critical thinking!

While reflecting on my methodology and my recent findings, I realized that I was following a pattern, a methodology, so in this article I try to describe that methodology, which I’ve called "Exploiting the Feature Factory", which you'll understand later.

To understand what a Feature Factory is, you first need to understand certain business concepts.

Growing beyond the core

When a company isn't big enough (small or medium), it focuses on a niche and usually doesn't venture beyond it.

For example, a small domain hosting company dedicates itself exclusively to domain hosting, focusing all its efforts on improving its product/service in its niche to gain more market share.

However, when companies grow enough, they reach a point where to keep growing they need to carve out a space in emerging economies (diversification).

They have one main niche, but they start to offer more and more services in other niches, even some that have nothing to do with their main niche (core).

According to my macroeconomics analyst bureau (,

,

), this is known in economics as:

Growing beyond the core

This strategy is implemented to increase growth opportunities and reduce risks from depending on just one main business.

In this way, when this domain hosting company grows large enough, it dedicates itself to:

- hosts domains

- hosts websites

- has an AI website builder

- sells cakes

- offers SEO services

- offers cloud storage

- sells donuts

...

But what does this have to do with the Feature Factory?

What the h*ck is the Feature Factory

Now that we understand the diversification strategy companies implement to keep growing, we can see what the Feature Factory is.

Well, the Feature Factory is a concept in product management that refers to a company that doesn't stop releasing features, without evaluating whether they really add value to the user or the business.

"Make this thing" VS "Figure out what we need to make, then make it"

However, in this article I'm referring to a different idea.

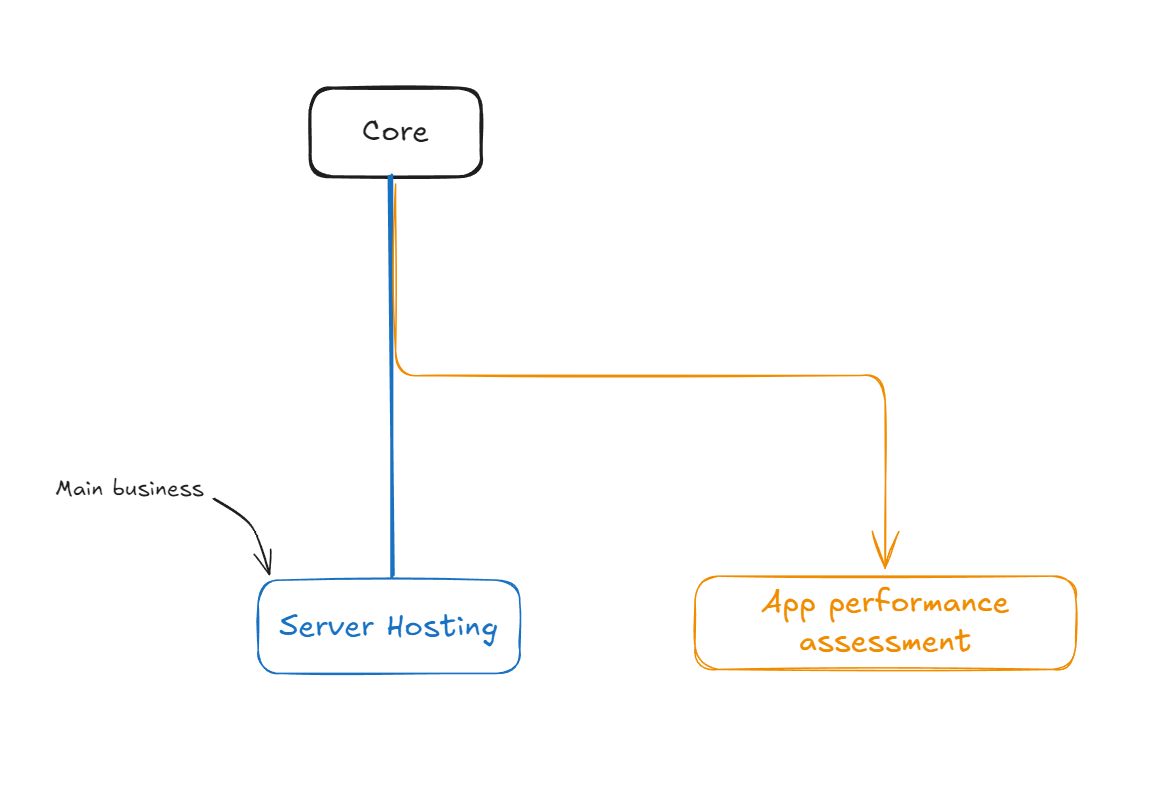

Think of the company "My Cool Business & Associates". This company is dedicated to offering servers (☁️), for example.

However, this company has grown enough in its main niche, and its growth now appears to be stagnant or slow, so in order to keep growing, it is going to implement the "Growing beyond the core" strategy.

As part of this strategy, "My Cool Business & Associates" is also creating an App Performance Assessment service.

We can see this service as a separate branch:

"My Cool Business & Associates" has server hosting as its main business or core, that's where it gets the majority of its profit.

But since its growth in that niche is already limited, it has created a new branch by opening a new app performance diagnosis business in another niche.

The important thing is that the new branches (services) being created already have an established market (since nowadays everything's already been invented) with strong competitors.

And that's why if "My Cool Business & Associates" really wants to enter the market, it must implement a very aggressive SDLC.

In software engineering, Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) is the process that guides how software is planned, developed, tested, and maintained.

What it means to have an aggressive SDLC is that the company will release features non-stop, continuously, features and more features...

As if it were a feature factory instead of an application/service.

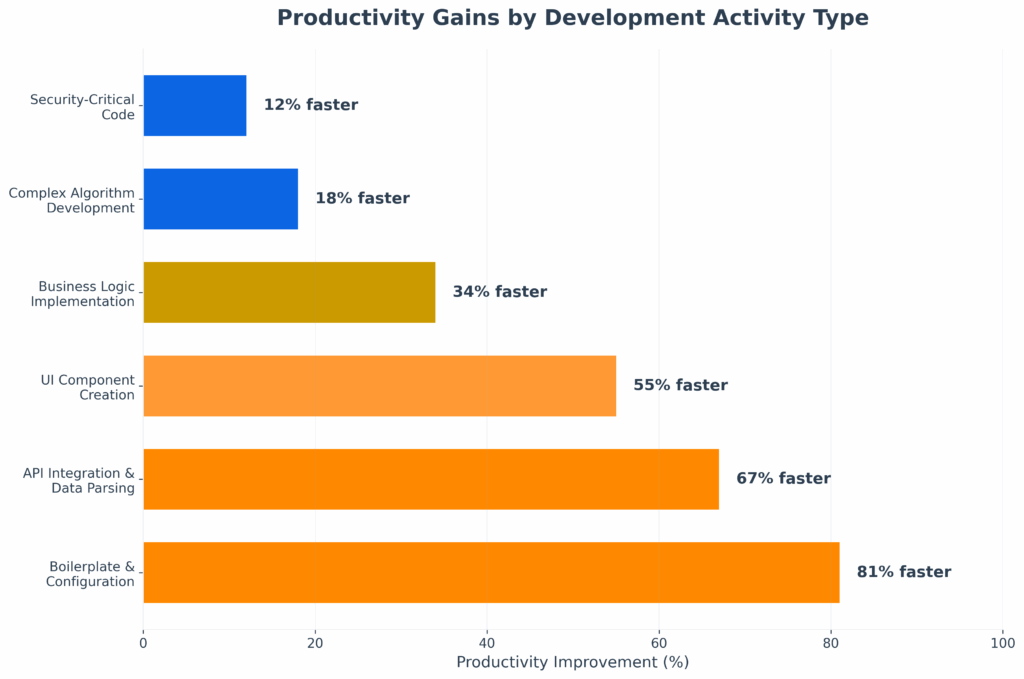

This approach is closely tied to an aggressive SDLC, where speed and continuous delivery are prioritized over thorough testing and security.

Aggressive SDLC → speed over quality

In bug bounty, the less time a feature has been live, the more vulnerable it is, since fewer hackers have exploited it and fewer tests have been done. This is the beauty of Exploiting the Feature Factory.

As a result, the company keeps releasing new features to remain competitive, and due to its aggressive SDLC, many of these features are deployed with a significant number of vulnerabilities.

Additionally, with the rise of agentic/vibe coding, these feature factories will produce new (and even worse-coded) features at an even faster pace.

That’s why this methodology focuses on exploiting these applications, rather than the company’s main application or service.

Normally, some conditions to identify these feature factories are:

- They have between 1-3 years of lifetime

- They're not the company's main business/product

- They have strong hype marketing campaigns

Note that this article focuses on Feature Factories because, although the main application also receives new features, the context is very different.

The key difference is that the core application or service follows a much more stable and long-lived SDLC. It is maintained by a development team that has been working on it for a long time, has already patched numerous bugs, and has built solid systems and processes around it.

And basically they have a strong product (💪).

In our example, "My Cool Business & Associates" has likely been working with servers for many years. They are familiar with common vulnerabilities, have established systems to detect and patch security issues within their niche, and even maintain a dedicated cybersecurity team.

In contrast, Feature Factories are much more immature. They often lack deep experience in the niche, rely on development teams that have not been working together for long, and operate without well-established security processes or defensive maturity.

So, as bug bounty hunters, what should the strategy be after identifying a Feature Factory?

Should we wait for developers to announce new features?

Absolutely not.

As we already know, features are more vulnerable the less time they've been live, and the least time they've been live is...

NOW

When they're still in development!

The features are already in production! You just don't see them (yet🙂↔️)!

Feature Flags

In an application with a reasonably professional development team, the changes the development team makes aren't exposed to end users just like that.

In my case, I can afford to push changes to the production environment directly, since I have a team of testers (they're called users).

But in an SDLC, a common practice is to use Feature Flags or Toggles.

These flags are switches in the code that are checked at runtime to enable or disable functionalities.

For example, if a development team has been working on a new search functionality, there might be a flag called:

// .env

NEW_SEARCH_ENABLED = false;

and at runtime it's checked to know whether to use the new feature or not:

if (!!process.env.NEW_SEARCH_ENABLED) {

useNewSearch();

} else {

useOldSearch();

}

This applies to any type of feature, although they're normally not in code, but in other environments like:

- Environment variables

- Databases

- External services

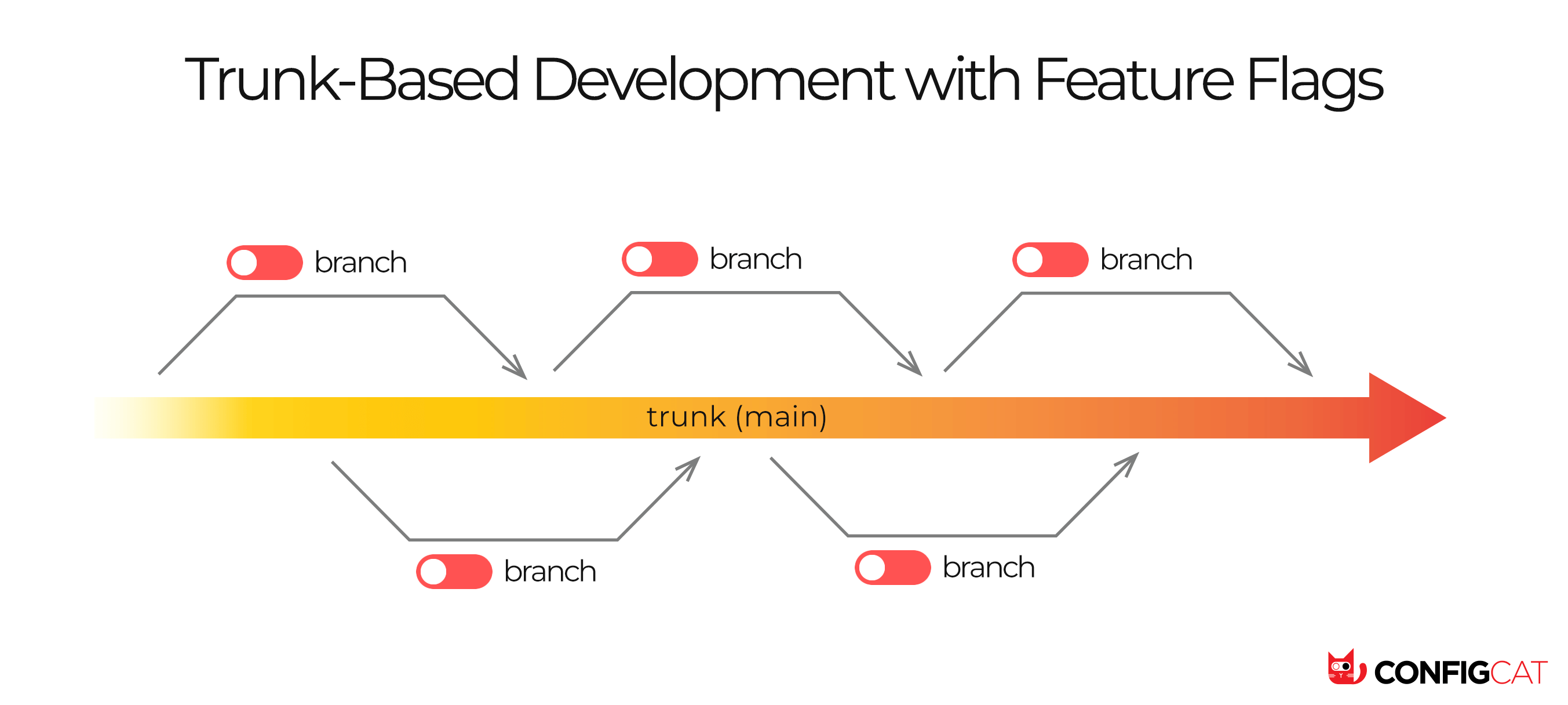

Feature flags allow you to do many things in development like canary launches, A/B testing, kill switches... But what interests us is that a common practice of using them is for Trunk-based development.

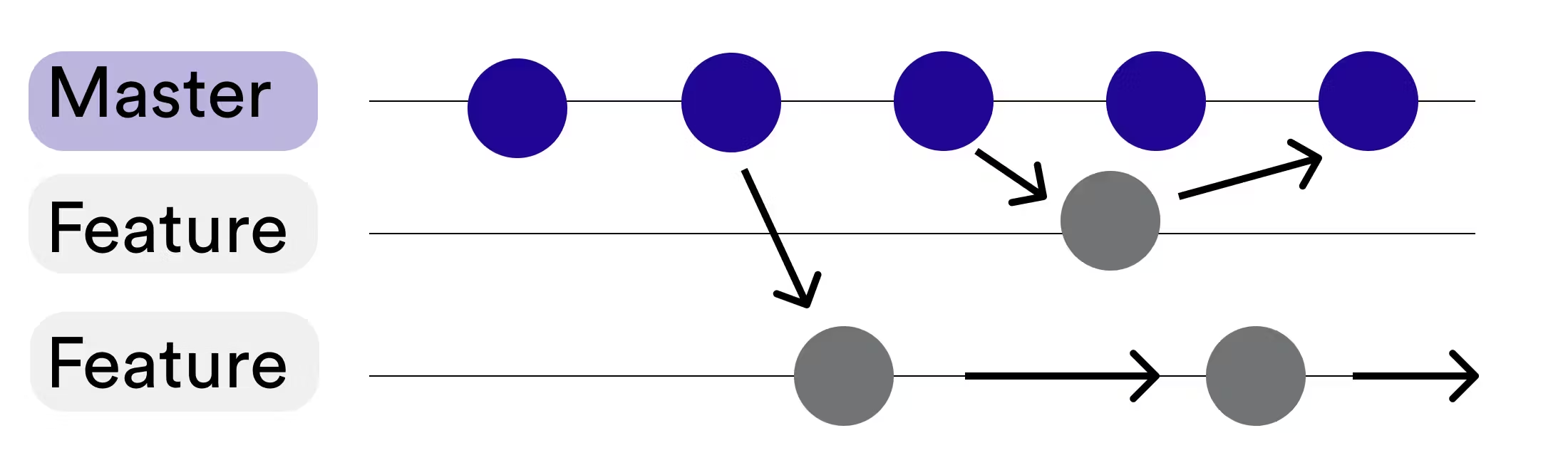

Trunk-based development

If you've worked on a team project, you know that the usual practice to maintain good version control () is to create branches for each feature being developed:

However, in applications that aren't simple and that have an aggressive SDLC (a Feature Factory✨), this methodology causes long development branches, which in turn cause:

- complex merge conflicts

- bugs that are difficult to debug

- deployment delays

...

And basically they complicate continuous integration.

Trunk-based development consists of using feature flags so that the whole team can work on a single main branch (usually main or trunk) and avoid long branches.

Feature flags are used, for example, to upload a feature to production but keep it hidden from users.

Security by obscurity👁️🗨️

For example, if a development team is working on a new feature, a workflow might be:

- All developers work on their features on

mainor in very short branches - The code is merged quickly to the main branch

- The functionality is hidden by a flag (which only activates for developers)

- The code is deployed to production continuously

- The flag is activated only when the new feature is validated

However, if we, as attackers, discover a feature flag and manage to activate it, the situation changes completely.

We will likely start seeing new UI elements, newly loaded JavaScript modules, new endpoints, and entirely new flows.

Many of these features (due to an aggressive SDLC) aren’t even production-ready, yet they are pushed to production anyway!

So now you can start to see the idea!

Feature factories are products that aren't from the company's main niche, so they need to release many features to gain market share and be competitive.

Since they have an aggressive SDLC, trunk-based development is usually used, which forces features to reach production when they're still in development.

Unvalidated features are hidden from users through feature flags until they're ready.

Feature Factory

↓

Many features

↓

Aggressive SDLC

↓

Trunk-based development

↓

VULNERABLE FEATURES IN PRODUCTION✨

Unfortunately, there's only one problem for this development strategy.

Hackers don't like feature flags🏴☠️

Attacking Feature Flags

A feature is more vulnerable the less time it's been live, and as we've seen, in Feature Factories when they're most vulnerable is right now, since they're already in production, yet still partially under development.

We hackers don't like being told what we can't do, and we absolutely refuse to be told whether we have a feature enabled or not, so we just enable it ourselves!

There are real treasures in these features under development, so as hackers we want to access them.

It’s worth noting that, normally, the main application or service also uses feature flags to hide features under development.

However, the key point is that (at least in my experience) feature factories, due to a rawer development team and a more aggressive SDLC, tend to expose significantly more vulnerable features.

I’ve exploited code that looked more like something an insider had pushed than something produced through a proper development process.

Sometimes I felt that by reporting certain vulnerabilities, a junior developer might get fired or sent to the coffee machine (☕).

There are many ways to use feature flags:

- Hardcoded

- Environment variables

- Third-party services ...

But in the end, they're just boolean variables!

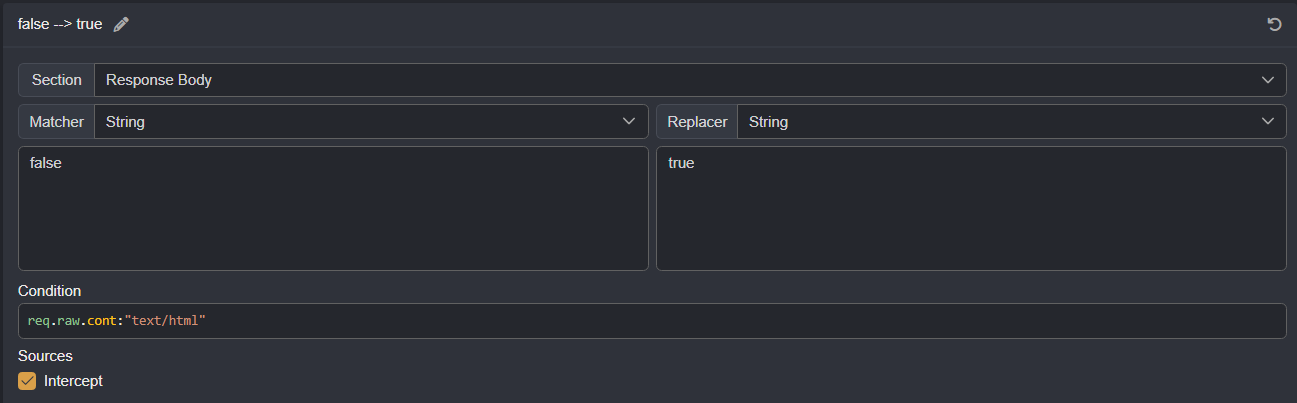

A trick that works many times is to design and configure a deliberately complex rule, meticulously crafted and finely tuned in your proxy's match and replace, so that it covers multiple scenarios and possible variations:

Mmm well, that's it...

Since they're boolean variables, simply changing false to true we can access most of the time a lot of features under development.

It's really not that easy since many times with this rule we'll break the application. A workaround is to do it only on the first request.

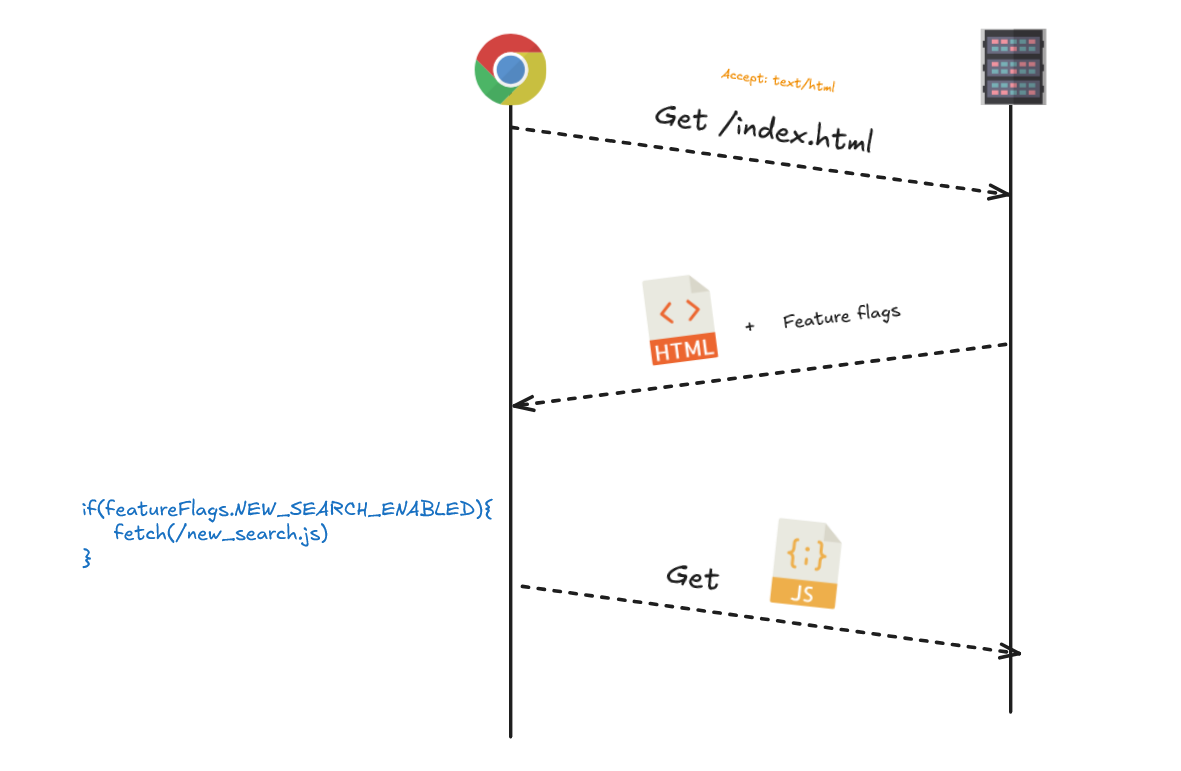

Feature flags need to be available from the first render so that the application doesn't have visual glitches and doesn't have to load unnecessary JavaScript.

That’s why they usually appear in the initial HTML, before the JavaScript with the features loads, that is, in the first request.

Feature flags are usually injected in the initial HTML, then the application on the client will read the feature flags and load the necessary JavaScript and display one UI or another.

The first request in modern applications (SPA) is the one that returns the HTML and the request contains a header like this:

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

So if we set the match and replace rule to:

req.raw.cont:"text/html"

We'll only change the boolean values of the feature flags (false → true), activating features under development and preventing the application from breaking, by avoiding accidentally intercepting other types of requests like XHR requests.

Note: Not all feature flags are always delivered in the initial HTML. In some cases, flags are dynamically resolved through XHR requests to the API (for example, user-dependent flags like

isAdmin, plans, cohorts, etc.).

Each application implements feature flags differently, so there's no universal methodology that works 100% of the time. However, intercepting and modifying only the first HTML response usually covers the most common case, especially in modern SPA applications.

However, leaving that rule enabled can break many parts of the UI and make it unusable.

Personally, I enable that general rule in the proxy, analyze how the UI behaves, the new modules that are loaded, and the new API requests the application makes, and then focus on a particular feature that might have an impact.

Once you discover a feature that might be interesting, the next step is to focus on that feature and experiment with the flags to determine which one(s) activate it.

You should then modify only that specific flag (🚩), in order to avoid breaking the application and to be able to exploit the feature comfortably.

You can do this by looking at the HTML request in your proxy and comparing the changes from the original request with the one modified by the match and replace rule.

The truth is that depending on the application, identifying a specific flag can take little time, a lot of time, or be impossible.

Some flags are called:

advancedDomainRegistrationEnabled

and others can be called:

adre

From my experience, agents are usually good at identifying these feature flags if you give them the bundles and the HTML, so I recommend using agents like Claude Code or Copilot to deobfuscate a feature and be able to modify only that flag.

Personally, I download all the application bundles into a single folder and run my coworker:

claude -c --dangerously-skip-permissions

My coworker generates Markdown summaries explaining each feature I ask for, including endpoints, deobfuscated and parsed code (it even runs it through ESLint).

I still need to refine the subagents I’ve created, and once they are properly polished, I’ll publish them.

Exploiting Feature Factories

In this section I'm going to narrate some examples of vulnerabilities I've found.

I was hunting on a company called MegaCorp. This company is dedicated to a specific niche with its primary.app application.

MegaCorp is a very large company in its niche, so some time ago it started with another secondary niche with the secondary.app application.

However, the secondary.app niche has an already established market and high competition, so if MegaCorp wants to enter the market, it must turn secondary.app into a feature factory, for example, by collecting features that users request in other applications on the market.

That way it can gain market share and attract users to its application, growing in the niche.

I'm the main app guy, I don't even do recon. My strategy is to understand an application very deeply, to become one more developer.

I even follow the developers on X to feel like one of them... I'm not crazy, I promise...

Something I recommend for this strategy is to follow MegaCorp and secondary.app on all social networks, since feature factories often have strong hype marketing campaigns.

These campaigns usually have posts like:

"We're excited to announce a major upgrade coming to Secondary App next week!"

This already tells you that they've probably pushed hidden features with flags to production.

This was my case a few weeks ago...

I was procrastinating watching a movie after a long day of disastrous hunting. However, since I'm subscribed to notifications on all social networks for secondary.app, I got a notification from X.

I immediately opened Caido and went to the application to investigate the features.

This Feature Factory hunting strategy is effective if you know the application. Since I already knew it like one more developer, when I made the change from false to true, I immediately started seeing requests to new endpoints I had never seen before!

In my case, I focused on one particular feature.

One of the features I discovered was "Import from GitHub". You could say it was impact at first sight💘.

That's where I thought there could be more impact, so I started working on that feature.

primary.app allowed GitHub integration, and most of its users were alredy using that integration (since it’s the standard), so it was only a matter of time before secondary.app integrated it as well.

There are two ways to efficiently allow GitHub integration in your application:

- GitHub OAuth

- GitHub App

Using GitHub OAuth is the correct way to ensure that GitHub RBAC is applied, since all operations are performed with the permissions granted by the user’s access token.

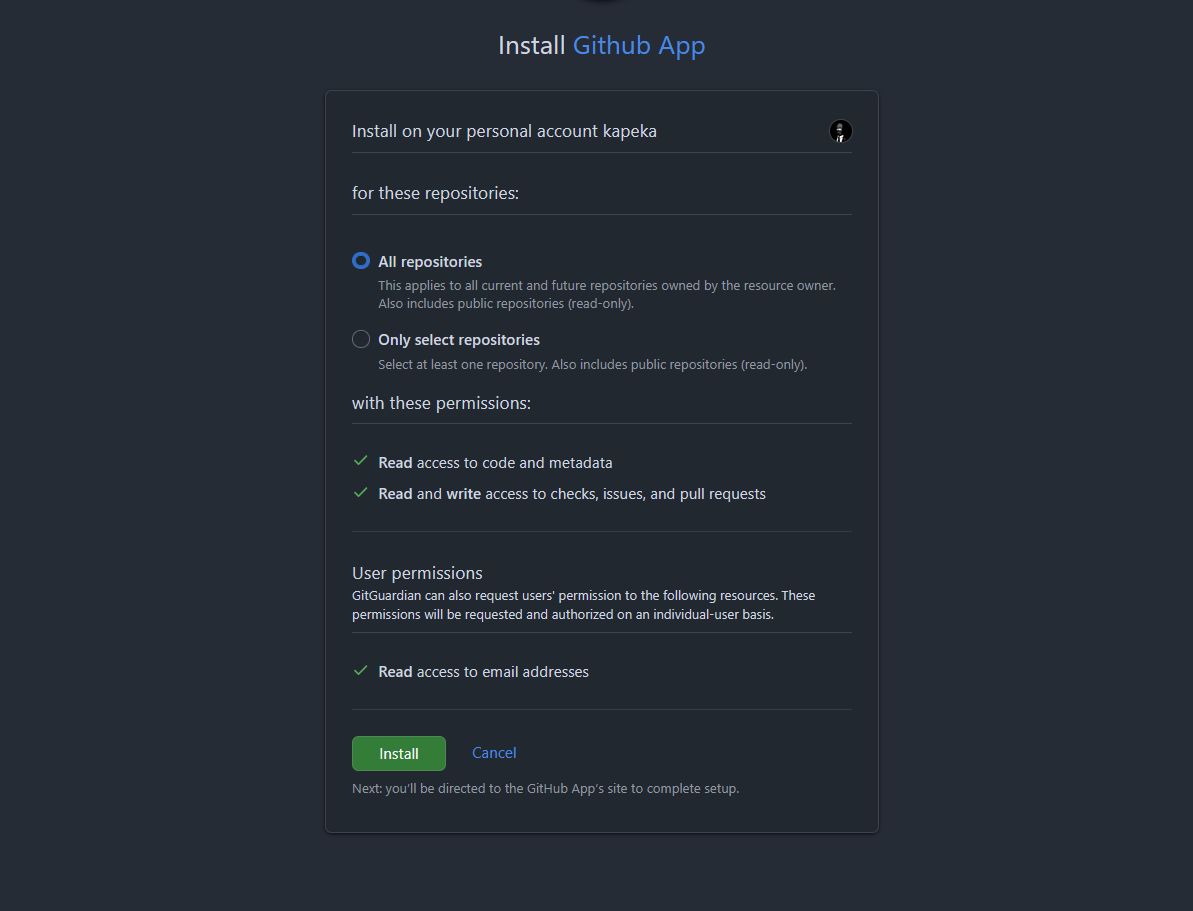

However, many third party apps need to implement bots and background tasks on users' repositories, and that's why many applications, in addition to GitHub OAuth, implement their own GitHub App.

A GitHub App acts on your GitHub resources with the permissions you grant it when installing it, which by default is full access (read & write) to all repositories (root💀).

So my idea was clear: try to exploit the application’s background tasks to see if I could interact with other users’ private repositories (who had installed the GitHub App) with elevated privileges (GitHub App permissions).

Well, to my surprise, I didn't even have to complicate things looking for background task flows. I found an endpoint the frontend used to view a user's repositories:

GET /git/repos?user=PRIMARY_APP_USERNAME

Just like that, no complications, an IDOR that allowed me to see the title, description, and metadata of private repositories of any user who had MegaCorp's GitHub App.

Never grant full read access to your repositories for any GitHub App; eventually, the app is going to be hacked.

Since usernames in primary.app are public, I could enumerate private repositories belonging to any user. For example, I could do a quick search on and collect tons of usernames, including the company’s CEO!

This was cool, but it didn’t have much impact either (aside from seeing which private projects people were working on).

However a while later I found a way to interact with the private repositories, clone them and push changes!

// import repo

POST /git/repo

{

"namespace": GITHUB_USERNAME,

"repo": GITHUB_REPO_NAME

}

// push changes

PATCH /git/repo

{

"branch": REPO_BRANCH

// complex body that doesn't matter

}

I could clone and interact with a user’s private repository (push changes, create branches, PRs…) just by knowing their username and repository name, which I could obtain from the previous IDOR!

This had a brutal impact. Imagine being able to clone and push changes to any private GitHub repository using the vendor GitHub App as a bridge to bypass GitHub RBAC!

Imagine pushing changes to the main branch of a large OSS project/library (💀)!

Key Takeaways

I’ve found many more bugs using a very similar approach, some of them with even higher impact in terms of CVSS metrics.

However, this one felt like the coolest and silliest example, since, as you can see, these aren’t complicated bugs or crazy workflows, just a matter of understanding the software, its lifecycle, and knowing where to look.

From all of them, I ended up extracting the following methodology:

-

Identify the Feature Factory: First, you need to identify your target’s Feature Factory. This is usually a secondary product or feature where the company is pushing hard to gain market share. It is the area where growth, experimentation, and rapid development are most visible.

-

Know the application: Become an expert on the application. You should understand it as if you were another developer working on the project. This allows you to notice even subtle changes and puts you in a position to hunt issues before others do.

-

Monitor social media: Keep a close eye on the company’s and developers’ social media accounts. Marketing campaigns and update announcements often indicate that new features have been pushed (not yet visible to users), many of which may remain hidden behind feature flags until tested by the dev team.

-

Understand the flag system: Learn how the application implements and manages feature flags, and what each one activates. This way, when you discover a new flag, you can focus on exploiting it directly and comfortably, without breaking the application in the process.

-

Monitor Flags: Every application has a flag system that comes in different formats, so you can easily write a script in 15 minutes to extract them and get notified when a new one appears. I’m currently building a tool for this, but I haven’t had time to finish it yet, once it’s done, I’ll update the article.

-

Think critically (🧠) !

Caveats of feature factories

There are certain disadvantages of attacking Feature Factories. The main one is that by having an aggressive SDLC, changes are pushed to production constantly and very quickly.

They even deploy on Fridays 💀

"like, who the hell deploys on Fridays???"

These changes don't just implement features, they also modify them.

Which means that one day there might be a bug, and the next day it's gone...🥲

That's why it's important that you make a descriptive and very simple report so the triager can validate it quickly. Otherwise, the vulnerability might get fixed before the triage attempt and you'll get a:

🌷Issue is not reproducible🌷

In my case, I made a very confusing report on the GitHub vulnerability and it took a month and a half to triage!

During that month and a half, the vendor was implementing changes and patches. Fortunately, I was able to bypass them all, but the severity ended up dropping from Critical to High😒.

But this is exactly what I mean in this article, Feature Factories are so focused on shipping feature after feature that they sometimes push absolute monstrosities straight into production.

In many cases, because the development team hasn’t been around for long, there’s a significant lack of coordination between the security and development teams.

This often leads to bugs being marked as RESOLVED even though there’s either no real patch at all, or the fix is very weak and easy to bypass.

Conclusion

I hope this article has been helpful to someone in some way.

I hope the idea comes across and at the very least makes you reflect and improve your methodology!

Feel free to follow me on X if you want, and happy hacking!

Thanks for reading!